An essay about the colonist propaganda in my childhood nostalgia, originally written for feminist magazine LOVER.

“I heard of the discovery of America, and wept with Safie over the hapless fate of its original inhabitants…”

– so says the Frankensteinian creature in Mary Shelley’s 1818 masterpiece.

As noticed by many scholars before me (eg Burkhart 2020), some of these “red flags” in Frankenstein show striking similarities with contemporary indigenous feminist assertions. Think for example about Shelley’s use of the word “savage” which is rooted in a tradition of racist references to Native Others, and also supports arguments of the story as an allegory for the brutality of England’s imperialist “social mission” (for more about this, see Spivak 1985).

In Shelley’s novel, the points of view of the oppressed characters are not to be missed. This is very different in the two works that first introduced me to two Native American cultures: Pocahontas (1995) and The Little House on the Prairie (1935, in the Dutch translation of 1975). As these two examples are still popular today, in this essay, I will provide a short but critical reading of each of them, and explain why media like these are highly problematic. Unfortunately, I have not yet managed to reach someone from a Native American background to have them read and comment on this essay, but nevertheless, I hope that this writing can be a first step for me to be an ally.

Pocahontas or: how to transform a life of suffering into a fairy tale

In the 1995 animated Disney film, the beautiful young woman named Pocahontas could take good care of herself, living in perfect harmony with her surroundings, while singing beautifully. OK, I admit it: I had a childhood crush on Pocahontas. That is, on the free-spirited character from the original movie version (1995), for in the sequel, she was reduced to something animalistic – “she came down from the trees!” – that had to become a dress-up doll, disguised in garments in which she can hardly move, just to please the powerful men in her life.

In the original movie, Pocahontas is friends with the animals, the trees and even the stones and the rivers. What’s not to like? As an adult, I found out that the story that Disney told me about Pocahontas is super problematic and far from being historically accurate. It is a lack of respect for the memory not only of Pocahontas, but of all the Native Americans who went through equally tragic lives. Of course, films are known to take certain creative licenses to reach larger audiences and sell attractive products to the general public. In the case of the animated Pocahontas film, however, this is controversial as historical omissions and changes in the tone and content of events hide the human rights violations that actually occurred. It is true that thanks to the film, entire generations of children, most of them now adults, know the name of Pocahontas, but it is also true that most of them only know the Disneyfied version of her story and nothing about the historical figure of Pocahontas.

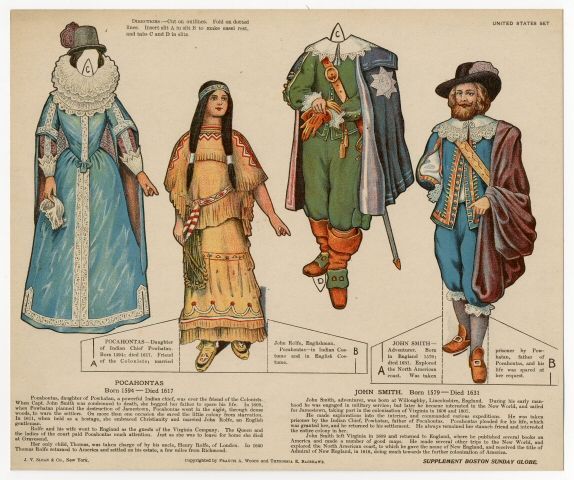

This Disneyfied story of Pocahontas is based on the life of a 17th century Native American named Matoaka. Her father was Wahunsenaca and her mother Pocahontas, from whom she would inherit her name (probably after her death). Behind the friendly story, the romance, the fun and the adventure on screen, there are aberrant and truly monstrous facts. According to the research and interviews conducted by Vincent Schilling with Virginia tribes and direct descendants of Pocahontas, she was kidnapped by the English and made hostage; she became pregnant after being raped multiple times and she gave birth to a son named Thomas while she was in captivity and was later separated from him; she was stripped of her land (she was taken to London to prove that the natives could be “domesticated”), her Powhatan religious beliefs (she likely believed in many different gods and spirits, among others the provider Ahone and the evil Oke, but was forced to convert to Christianity) and her name (when she married John Rolfe she was renamed Lady Rebecca Rolfe). As if this were not enough, Pocahontas died before her 21st birthday, and some sources indicate that she was probably poisoned while she was in England (Schilling, 2017).

Learning about the horrors historical Pocahontas has experienced makes me wonder. How far can one go, rewriting history in such an intrusive manner it results in soften audiovisual content made for children mainly? Based on what has been analyzed so far, I conclude that those involved in the making of the Pocahontas movie never wanted to tell her story, they only seized her name to create a Native American Disney princess that was fun and sexy and whose story was framed in common patterns, like the happy ending of a fairy tale. Besides Pocahontas fulfilling her dreams of adventure, she also adopts the gender stereotyped role of the woman as chief nurturer for her community and a hidden message of the self-sacrifice of motherhood is integrated at the end of the movie (Dundes, 2001). It is necessary to use cruel and bloody representations of human nature in order to do justice to the historical Pocahontas. Her tragic story deserves to be known so as not to forget the suffering of the Powhatan tribe. This historical revisionism has troubling implications for the way Native Americans are treated by the US government today, and the cultural autonomy of Idigenous people more generally. The Disneyfied story of Pocahontas as the sexy, exotic Other promotes an image of a Romantic noble savage who exists to be conquered, captured and abducted. As that image contributes to the horrible fact that a disproportionate number of indigenous women are victims of sexual violence, just to name an example.

“How smooth must be the language of the whites, when they can make right look like wrong, and wrong like right.”

– From Black Hawk, Sauk

The Little House on the Stolen Land

One of my favourite book series was not much better. It was The Little House on the Prairie – a story that describes a family’s life on the post-Civil War frontier through the eyes of a young girl, Laura. The Little House was compulsory classroom reading in the elementary school I visited. During these reading sessions, I was regularly scolded by the teacher for not knowing where we had left off in class – but I couldn’t help myself, it was just too exciting, I had to read ahead and simply couldn’t wait for my slightly slower-reading classmates! I fell in love with the cosy family life and I adored Laura, the brave and rebellious young explorer, for breaking the rules, blazing her own trail with an extreme confidence in her own ability and worth. I also thought it would be nice to live in such a simple manner, looking after the animals, cooking dinner from your homegrown veggies and learning. Little did I know about the brutality behind this cosy world.

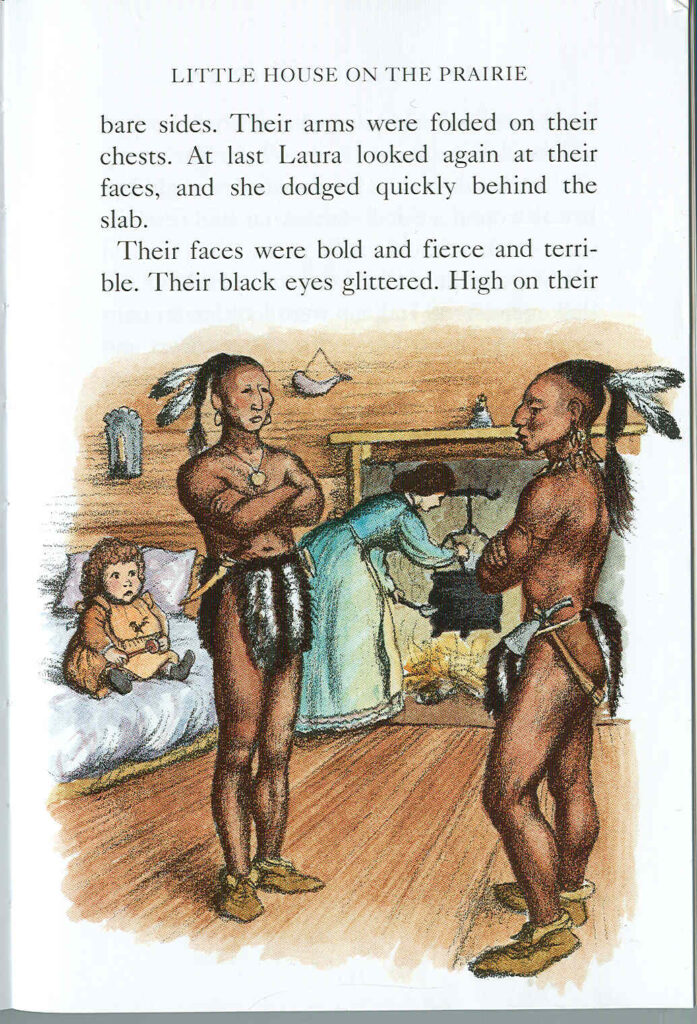

Using money from the government, Laura and her family – Pa, Ma, Mary and Carrie – moved to the section of Kansas that was once called “Indian Territory”. As a child, I did not realise that this makes them illegal squatters on Osage territory, which the books described as a “free” land where there were “no people, only Indians”. And those “Indians” were often described rather animal-like (as “wild”, “fierce”, “yipping” and more stereotypical dehumanizing terms) or even plainly demonized (mostly by Laura’s mother, simply called “Ma”, but also by a neighbour, who states that “[t]he only good Indian is a dead Indian”). In between the lines, a character might utter a more enlightened and nuanced approach towards the Native Americans, such as Laura’s father, Pa, who admires their outdoorsmen skills, but admiring a stereotype is a very common racist deflection. Altogether, in my recollection, The Little House remains a book full of contradictory messages, just like the TV series, that made the “savages” more “noble”. Even when you ignore incidents as beatings and horse theft, seemingly ordinary families like the Ingalls were crossing the line as well. They stole resources from the natives: they broke Osage land to farm it, they built their houses and dug wells on Osage domains and they hunted animals in Osage woods. This act of squatting in itself was a major injustice.

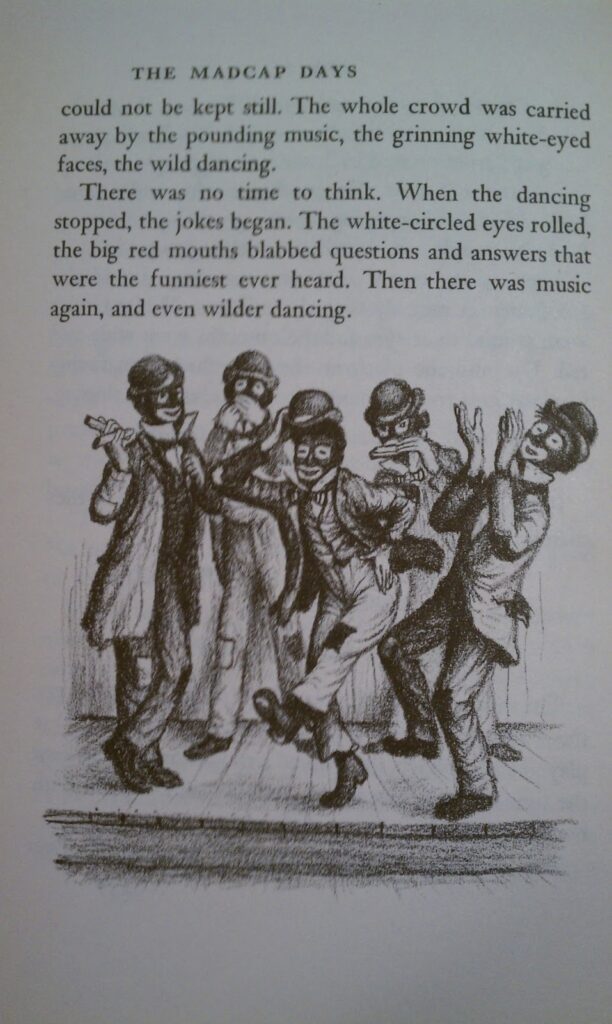

It would go beyond the scope of this short essay to list all the colonialist and morally reprehensible instances from the books, so I’ll leave you with one last example, of Blackface. I vividly remember this scene, in which Pa dresses up to perform in some sort of Minstrel show. I remember how I could relate to Laura, who wondered whether this “darky” could be her Pa, just as I had to look twice before I recognized my own father as Zwarte Piet. Such a recognizable and cosy scene, I hadn’t the foggiest idea about the unethicality of it all.

New Perspectives

These are matters that need to be put right. As fairy tales in disguise – or even propaganda disguised as fairy tales – stories such as Pocahontas and The Little House presented us with a sickly unfair world. I lived in this world, not only passively, but also actively, by passing on these stories and participating in our social relationship to culture that is completely made of consumerism and utilism. As if a culture only has the value we assign to it (it is all about “is it nice or not nice?”, “do I have to pay for it?” and “what can I get out of it?”). Without realising it as a child, I participated in a system of colonialist perspective and control. As if the value of a culture depends on what we – the oppressors – think of it. As if we have the right to relate to other cultures in this way, to make money out of them and to make decisions about them.

Now, it is our responsibility to grow in unraveling what constitutes cultural appropriation, how it hurts those it seeks to celebrate, and how to be inspired by a culture without insulting it. For when you know better – you do better. We cannot and should not let these cultures be lost in Disneyfication. The internet enables us to learn more from and about Native American tribes – like the Osage, Powhattan, Haudenashonee, and Anishinaabe. We can study their languages, read their stories and listen to their voices. Through distortions, falsifications and corruptions of histories, inaccurate representations are marginalizing and infantilizing Native American cultures, but we can and should educate ourselves about the horrible oppression of many (vastly diverse) tribes in present-day America. The two examples discussed may look like innocent children’s television, in aesthetic terms, but in content they are propaganda.

What we should be concerned about are the ways that actual indigenous Americans are harmed today, by oil pipelines, political neglect and police brutality to name just a few examples. COVID has a massive death toll on reservations, and the Border Wall desecrates Native American lands in Southern California and Arizona. However a series like Little House or a Disney film may not seem connected to these political issues, they do represent the broader view on matters like these. This perspective resounds all the way to the global political stage.Movies like Pocahontas hide this, trivialize it, make it seem inevitable or even like it’s in the past. Pocahontas is not just a Disney princess, she is a victim of imperialism used to feel better about the way things are for Native Americans today.

References

Burkhart, Emily. 2020. Lessons from Monster(s): Postcolonial Feminist Analysis of Frankenstein: The 1818 Text. Retrieved from: https://hilo.hawaii.edu/campuscenter/hohonu/volumes/documents/LessonsfromMonstersPostcolonialFeministAnalysisofFrankensteinThe1818Text.pdf

Dundes, Lauren. (2001). Disney’s modern heroine Pocahontas: Revealing age-old gender stereotypes and role discontinuity under a facade of liberation. Online: https://www.joycerain.com/uploads/2/3/2/0/23207256/disneys_pocahontas_and_gender_stereotypes.pdf

Hynes, Ashlee. (2010). Raising Princesses? Gender socialisation in early childhood and the Disney Princess franchise. Critical Social Thinking: Policy and Practice, Vol. 2, School of Applied Social Studies. University College Cork. Online: https://www.ucc.ie/en/media/academic/appliedsocialstudies/docs/AshleeHynes.pdf

Schilling, Vincent. (2017). The True Story of Pocahontas: Historical Myths Versus Sad Reality. Online: https://indiancountrytoday.com/archive/the-true-story-of-pocahontas-historical-myths-versus-sad-reality-WRzmVMu47E6Guz0LudQ3QQ

Spivak, Gayatri Chakravorty. 1985. “Three Women’s Texts and a Critique of Imperialism.” Critical Inquiry, vol. 12, no. 1, p. 243–261. www.jstor.org/stable/1343469 .

Image courtesy of the NMAI Photo Services Smithsonian Institution.

1 thought on “Nullifying the Native”