Holy Corona?

Amidst the corona virus pandemic, there is considerable evidence pointing towards the existence of a second century woman, who came to be believed to be the patron saint against plagues and epidemics. Her name? Saint Corona. This blog post explores some of the traces of this intriguing female saint.

According to tradition, Corona suffered martyrdom at the age of 16, around the time of the persecution of Christians, together with the also canonized soldier Victor of Siena. While Victor was being martyred, Corona,who was believed to be the bride of one of his comrades, is said to have comforted and encouraged him. For this reason, she was arrested and interrogated. The legend of Saint Corona states that she was killed by being tied to two bent palm trees which tore her apart as the trunks were released. Victor is said to have been beheaded. Some sources report that Corona was Victor’s wife. She might be linked to epidemics, however, there are also scholars who argue that the saint is more associated with treasure hunters (Miller, 2020).

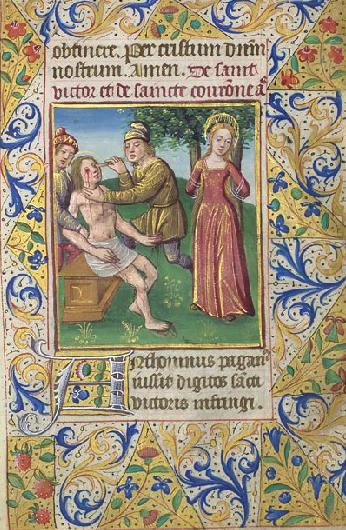

The surviving imagery of Saint Corona includes the illuminated miniature shown above. This full leaf depicting the martyrdom of Saint Victor and Saint Corona, can be found in a Book of Hours from Paris (France), ca. 1480. A book of hours is a Christian devotional book that was popular in the Middle Ages and the most common type of surviving medieval illuminated manuscript.

In terms of historical evidence, little is known about the saint in question. She is listed in the Roman martyrology and the Hagiography of the Church (Ballam, 2020). According to these records, Saint Corona was only 16 years old when she professed her Christian faith and prayed for a man named Victor before they were both martyred for their Christian faith during the reign of Marcus Aurelius (170s CE), in Roman Syria (Peterson, 2020).

Nonetheless, there exists disagreement in various texts concerning the site and date of martyrdom. Some texts cite Damascus, while Coptic sources cite Antioch as the place of the saint’s death. Other sources state Sicily or Alexandria as Corona’s place of martyrdom. Coincidentally, it has been reported that the remains of Saint Corona are preserved in Anzu in Nothern Italy, which is the hotbed of the corona virus in Europe.

As mentioned previously, the saint is largely associated with treasure hunters. In popular folk treasure magic, she was called upon to bring treasure to hunters and sent away through elaborate rituals (Dillinger, 2011). This resonates with her name, Latin for “crown”. Historically, Corona might have been called Stephanie (or Stefania or Stephana) from Greek στέφᾰνος, the Greek version of her Latin name, which also means “crown”. Presently, the saint is still invoked in connection with superstitions involving money such as gambling and treasure hunting.

During the 17th and 18th centuries, the Corona-Gebet or Kronengebet (“Corona prayer” or “crown prayer”) was a popular folk magic ritual, to locate hidden treasures. This spell can be found in several magic books, including the 6th and 7th book of Moses . The treasure prayer was sold by purported magical experts as a supposedly safe means of obtaining huge wealth. Early modern lawsuits however, did not locate this practise in the realm of magic, but rather regarded to it as a fraud. (Dillinger 2007)

The saint Corona and Victor are venerated and remembered on 24th November and their feast is on the 14th May (occasionally on February 20th as well). The saint is mostly venerated in Austria and eastern Bavaria, where various pilgrimages are dedicated to her:

- St. Corona am Schöpfl

- Wallfahrtskirche St. Corona (in Staudach)

- St. Corona am Wechsel

- Wallfahrtskirche St. Korona (in Passau)

- Wallfahrtskirche St. Corona (in Altenkirchen)

- Kapelle St. Corona (in Arget)

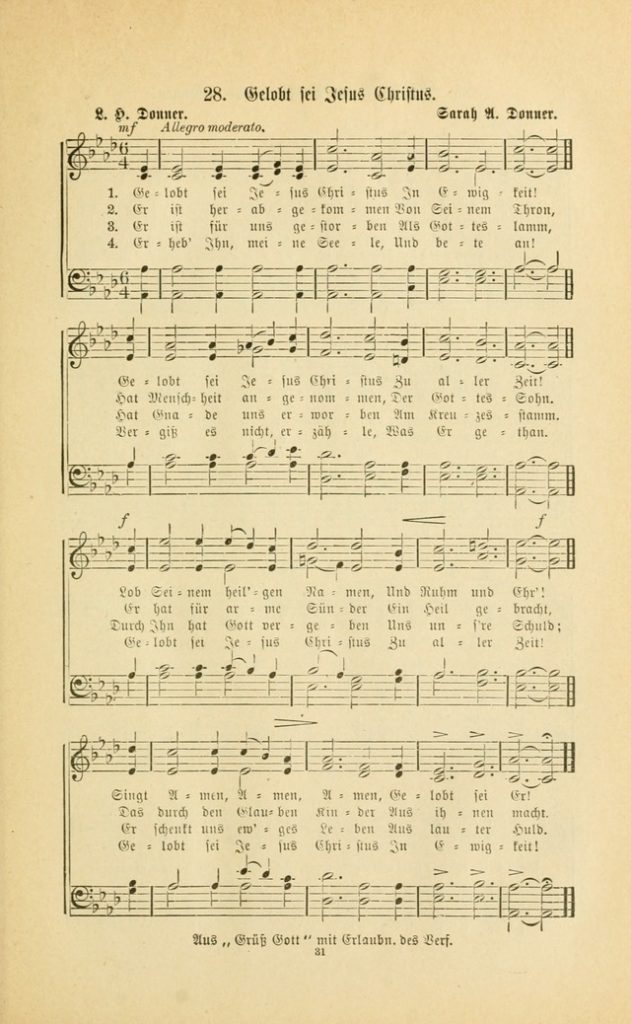

Saint Corona has her own song, handed down from the Lower Austrian town of St. Corona am Wechsel. This pilgrimage song is a contrafact to the melody of the hymn “Gelobt sei Jesus Christus in alle Ewigkeit”, which is shown above as it was published in the collection of “Frohe Lieder” (published by the German Baptist Publication Society, Cleveland, 1898). Furthermore, St. Corona am Wechsel reports of calls for steadfastness in faith, requests for storms and crop failures and the prevention of (livestock) epidemics, which is also taken up in the corresponding article of the Ecumenical Encyclopedia of Saints, but is not otherwise documented in the specialist literature. The information may go back to a local tradition in St. Corona am Wechsel, according to which the saint was called by the rural population against livestock epidemics.

There must have been an important “Corona cult” in the medieval cathedral of Bremen, as suggested there by pilgrim signs and three sculptures in the cathedral. She was also worshiped by Emperor Otto III, who after his imperial coronation in 996, had some corona relics transferred from Otricoli in Umbria to Aachen, together with relics of St. Leopardus. Both saints were consequently made patrons of the Aachen Marienstift . The lead reliquaries from the early 11th century were rediscovered in 1843. In 1911, their content was embedded in the newly created Corona Leopardus Shrine of the Aachen Cathedral, which is currently (March 2020) being restored.

The most popular depiction of Saint Corona is found in Northern Italy, on the slopes of Mt. Miesna, in the church of SS. Vittore e Corona. The saint is depicted in a column, wearing a small crown while elegantly supporting a larger crown with her hands and carrying a pair of palm branches‒ the trophy of martyrdom. This depiction of Saint Corona was created by the Master of the Palazzo Venezia Madonna. According to the Danish Statens Museum for Kunst (in Copenhagen), this altarpiece was created in (or immediately after) the plague year of 1348, which severely decimated the population of Siena.

References

Ballam, S. (2020). Saint Corona | Martyr of the Moment. Metropole. Retrieved from: https://metropole.at/corona-the-saint/

Dillinger, J. (2011). Magical Treasure Hunting in Europe and North America. Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 89–90

Miller, E.M. (2020). Is St. Corona the patron saint of pandemics? Religion News Service. Retrieved from: https://religionnews.com/2020/03/20/is-st-corona-the-patron-saint-of-pandemics/

Peterson, L. (2020). Yes, there’s actually a St. Corona! And her remains are in Northern Italy. Aleteia. Retrieved from: https://aleteia.org/2020/03/14/yes-theres-actually-a-st-corona-and-shes-buried-in-the-middle-of-the-pandemic/

Sauser, Ekkart (2004). KORONA aus der Thebais. In: Biographisch-Bibliographisches Kirchenlexikon (BBKL). Band 23, Bautz, Nordhausen, ISBN 3-88309-155-3, pp. 845–846.

Sauser, Ekkart (1997). VICTOR UND STEPHANIDA/CORONA. In: Biographisch-Bibliographisches Kirchenlexikon (BBKL). Band 12, Bautz, Herzberg, ISBN 3-88309-068-9, pp. 1349–1350.

Schmidt, L. & Beitl, K. (1994) Corona. In: Walter Kasper (Hrsg.): Lexikon für Theologie und Kirche. 3. Auflage. Band 2. Herder, Freiburg im Breisgau, pp. 1315–1316.

Spirkner, Bartholomäus (1938) Zum Corona-Kult. Bauernheilige und Patronin der Schatzgräber. In: Volk und Volkstum, Jahrbuch für Volkskunde. 3, pp. 300–313.

Wimmer, O. & Melzer, H. (2002) Lexikon der Namen und Heiligen. Nikol, Hamburg, ISBN 3-933203-63-5, p. 200.

3 Comments

Tim Shaw

Excellent, thanks for that

Maria

That’s quite an interesting story, I didn’t know all this info

Nicole Corrado

Really Imteresting! Shared in the Facebook group and page Neurodivergent Saints.