Rituals of an Urban Monk

As your typical Aspergirl, fixed patterns and structures are important to me. That is why I am so attached to rituals. They bring peace to my mind and give me something to hold on to when I am sad or confused.

Originally written for Bi Women Quarterly aka BWQ.

Whereas some other people with autism try to create predictability by doing things whose effects are foreseeable—turning the lights on and off, rolling marbles in the marble track for hours, asking questions you already know the answer to, etc.—I have my more traditional and hidden routines to offer me comfort in an overly difficult society. My personal rituals throughout the day are quite simple, and I only realize that they are rituals because it gets difficult when I cannot perform them. For example: like so many people, when I get up in the morning, I make and drink a cup of coffee. That seems trivial, but if for whatever reason my coffee cannot be there, my head short-circuits. Friends have often teased me about this presumed “caffeine addiction” and, while there might be some truth in there, there is more to it than that, namely, my ritual.

My love of rituals finds its place in two seemingly contradictory contexts: the church and the dojo. But regardless of the specific variety of social rituals these two places offer (and their diversity in time and space), they have more in common than they differ. All rituals we perform are characterized by an emphasis on form (the exact performance of an act is important), repetition (it is only a ritual if it is performed several times), and symbolism (ritual acts have symbolic meaning). Reduced to their essence, the existence of such ritual practices seems to be universal. At pivotal points in our life—the important moments that we cannot control like birth and death—rituals help us to be more aware and stay close to ourselves. Apparently, these practices are not as specifically autistic as the autism literature sometimes seems to suggest, and non-autistic people also derive and perform parts of their identity via rituals.

If rituals help shape and express identity, do they also have a place in sexual identity? Certainly, the use of make-up is such a symbol, and for budding sexuality there is a pop culture full of ritual songs and dances. That world seems far removed from the rituals in my church and in my dojo. Yet, in my view, sexuality and spirituality are connected to each other. In both experiences, you can reach a form of ecstasy. Christian mystics use erotic terms like ‘merging’ and ‘becoming one’ to describe their religiosity. Women’s magazines write about ‘mindful sex’ with tips and tricks that can be directly traced back to Zen Buddhism. For, as the Buddha apparently has said, “sex is the strongest impulse in man” and should therefore be practiced gently and with great attention. Rituals could help with that.

For me, not the sexual act itself, but writing about it is the ritual that shapes my sexual identity. An important pivotal moment for this ritual is, of course, Coming Out Day. A day to show that you feel safe enough to be vulnerable. That is easy for me to say: I live in the Netherlands and LGBT+ people have a relatively high amount of freedom in our country. You can have a relationship and marry someone of the same sex. In many other countries, of course, this is not the case. That’s why I use my writing as a ritual to keep focusing on this inequality, for which I need more than a day a year.

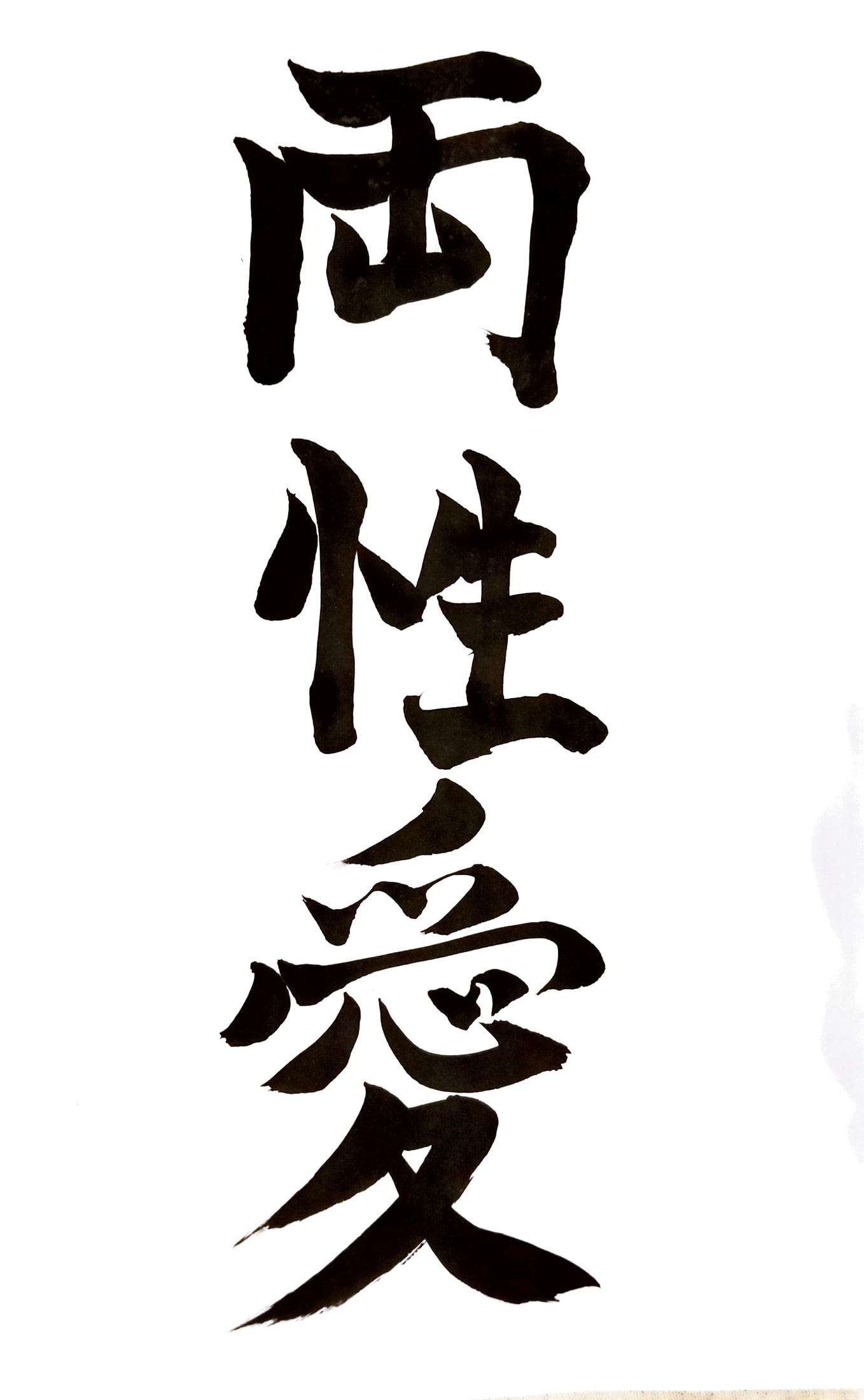

Although my church does have the ritual of the Gay Sing In, which I love, my ritual writing is usually not expressed in church or dojo. With candles and incense, I do Japanese calligraphy of words to meditate on, and computerized writing in three different virtual spaces: pre-written letters through Amnesty International, musings like this one for BWQ, and stories about my own sexual journey. Recently, a fourth form has been added, from an unexpected source. Inspired by a friend from my choir, I now regularly translate little poems. And sometimes they too contribute to my sexual experience, as in these short verses by the fifteenth century Zen master Ikkyu Sojun:

Vagina

Ikkyu Sojun

She has the primal mouth, but does not speak a word;

She is hidden in a magnificent forest of hair.

All living things lose their way in this forest,

But the countless Buddhas see the light there.

For me, this beautiful little poem resonates with the biblical texts of the Song of Songs, as I think that both are about expressing gratitude and celebrating life. My sexuality is a crucial part of my identity—and thus of my life. By reflecting on it through my writing rituals, with an attention similar to the way we meditate in church and in the dojo, I can further explore and celebrate my own sexuality, and hopefully also mean something to others. I hope that our rituals can contribute to sexual empowerment, as through reading and writing, we acquire knowledge—from the West and the East—about sexuality.

Our sexuality is an essential part of who we are. Deeply personal and intimate, as well as thoroughly embedded in our culture. Unfortunately, sexuality is still surrounded by taboos, stigma and shame—especially anything that is not hetero-normative. It often seems to me that there are no greater misunderstandings and crazy ideas about anything than sex. That makes me sad, for a good relationship with your sexuality improves everything: your love life, your self-love, your happiness level, your mood. You become a nicer person, a more attentive friend, a kinder partner. Through our writing rituals, like all these expressed in BWQ, we can give our sexual identities the attention they deserve and ultimately make the world a little better.

Featured image: Ritual Japanese calligraphy of the word “bisexuality”