A gorchest Prydain: The United Kingdom through Asterix’s eyes

Last year, my friend Wouter and I wrote this article for Kelten – the periodical of the A. G. van Hamel Foundation for Celtic Studies. With their permission, we now republish it in English. With many thanks to my co-author for his translation.

SUMMARY: Since 2008, the Welsh publishing house Dalen has been issuing translations of various Franco-Belgian comics into most of the Celtic languages, as well as into Scots. This article explores the Welsh, Irish, Scottish Gaelic and Scots translations of Astérix chez les Bretons. In its original form, the comic makes fun of British (especially English) customs as well as the English language from a foreign (French) perspective. The Celtic translations have engaged with the cultural and linguistic puns in rather different ways, reflecting the complicated relationship of each Celtic-speaking community with the English. While the Welsh translation focuses on making fun of the English language, the Scots and Scottish Gaelic translations are more overtly political. These differences may be said to reflect the different nature of Welsh and Scottish national identity: cultural and linguistic nationalism in Wales versus political nationalism in Scotland. Meanwhile, the Irish translation treats the Britons more like a foreign nation and largely avoids overt signs of resentment.

Franco-Belgian comics hold a great reputation. After the art form of the comic strip crossed over from the United States to Europe, it immediately spawned a tradition in the French-speaking world. As early as the 1930s, Hergé, with Tintin, oversaw the emancipation of the genre. Full-fledged, carefully-drawn adventures now took the place of short, entertaining cartoons.

After the Second World War, Asterix emerged, a comic by René Goscinny (story) and Albert Uderzo (drawings), set in Gaul shortly after the Roman conquest. The titular hero lives in a tiny village in Armorica, which, thanks to the magic potion of Panoramix the druid which gives its drinker superhuman strength, manages to keep the occupying power out. In spite of its grammar-school oriented humour, the story appeared to catch on in many circles.

The universal appeal of both Tintin and Asterix is apparent from the numerous translations made of these series. Translations into major (English, German, Spanish, Portuguese) and middle-sized languages (Dutch, Italian, Swedish) appeared very soon. However, the books have also appeared in numerous minor languages. Dalen Publishers from Tresaith, a village in Southwest Wales, has been publishing Tintin, Asterix, and other comics in Welsh since 2008. 1 As of April 2021, their catalogue comprises 19 Welsh Tintin translations (out of 24 albums in the original French) and 16 translations of Asterix (out of a total of 37, including collections and commemorative albums). The catalogue is expanded every year. Besides, Dalen also publishes Lucky Luke (Lewsyn Lwcus), among other series.

Since 2013, the publishing house has also occupied itself with other Celtic languages. That year, two translations of the Tintin album L’Île Noire appeared, one into Scottish Gaelic (An t-Eilean Dubh) and one into Scots (The Derk Isle). 2 Shortly thereafter, Asterix also appeared in both languages. Soon, translations of Tintin and Asterix into Irish came out, and in 2014 Tintin was even issued in Cornish.

In this paper, we will introduce the reader into the project surrounding these issues. First, we will draught a picture of the entire enterprise, afterwards we will, by means of the album Astérix chez les Bretons and its translations, attempt to show how the translators have made their own, Celtic version of this story.

Dalen: major plans for minor languages

The great man behind Dalen Llyfrau is Alun Cero Jones. Already in his youth, Jones was a fan of European comics and he began translating Asterix into his native language, first from English, later directly from French. Between 1976 and 1981, he had eight albums appear with Gwasg y Dref Wen. The series was then aborted and the books went out of print.

In the new century, Jones tried to revive the series. That was easier said than done. Major publishing houses were generally rather unwilling to do minor languages. The main purpose of these companies is, of course, making a profit; whoever wants to issue a translation, licenced or otherwise, first has to show he can cover the expenses. On top of that, Asterix was transferred to Hachette in the late 1990s. This, and various trifles around the future of Asterix (should the series be continued or not, now that Uderzo was aging and his last album was received very poorly?), delayed the making of a new Asterix series in Welsh. Only in 2011, preparations could begin; the year after, the first two albums appeared. By comparison, Tintin in Welsh began as early as 2008.

It goes without saying that issues in lesser languages yield lesser profit margins. On top of that, Franco-Belgian comics in the United Kingdom do not enjoy the popularity they have in France, Germany, or the Benelux. This means a Welsh translation will be sold even less than a translation into a comparable language from the continent (Frisian, for example). For all language series, the publisher needed to address public funds; private

donors, too, have contributed.

This applies to Welsh, but even more to the other languages that Dalen does. Welsh has hundreds of thousands of speakers and is still the first communal language in many places. There is an elaborate infrastructure supporting the language; issues like these comic translations are distributed to specialised Welsh book shops. The numbers of speakers for Irish and Scottish Gaelic run only in the tens of thousands, even though Irish is a compulsory subject in Irish (Republican) schools, which means there is a large group of non-fluent speakers. Scots does have millions of speakers, but the emancipation of this language only really started relatively recently. Many speakers consider their language an English dialect; the so-called linguistic volition is low compared to the Celtic languages.

Marginal languages offer an even bigger challenge. After the publicitary success of Tintin in Scots and Gaelic, Dalen was approached with the question whether this could be done for Cornish as well. It could, and in 2014 Tintin appeared in Cornish. But for a language with so few speakers (3000 at most), an entire series would be too much. There are now two Cornish Tintin translations; Jones expects no further expansion. Asterix in Cornish is

something for the distant future at best. The same applies to Asterix and Tintin in Manx or Jèrriais (the nearly vanished Norman dialect of Jersey).

The actual number of speakers is not the only thing that matters. As mentioned above, the status of Scots works to its disadvantage: relatively few speakers are interested in books in their language. For the Celtic languages, the opposite is often true: alongside the small audience of fluent speakers, there is a fairly large audience of readers who don’t know the language so well but are very motivated to maintain or expand their knowledge by reading it.

Outside the Celtic world, there is also a considerable market of collectors. They want to possess issues in as many languages as possible, no matter whether they can actually read them or not. This means there is a lower sales bound that new issues, when promoted well, will not fail to achieve. Evidence for this statement is provided, among other things, by Asterix translations into Mirandese (an Asturian dialect from Northeast Portugal with about 10,000 speakers) and various endangered Finnish dialects.

Astérix chez les Bretons

Our case concerns the eighth album from the series: Astérix chez les Bretons. This story was serialised in the Pilote comic magazine from September 9, 1965 and appeared in album form the year after. The story opens with the Roman invasion of Britain. Caesar organises a penal expedition into this island, that so often provided help to the Gauls in their war. As in Gaul, there is one village in Britain that manages to withstand the Romans. Unlike the Gaulish village, however, they don’t have a magic potion and will soon be overwhelmed by the superior strength of the Romans if nothing happens. One of the villagers, Jolitorax, has a cousin in Gaul (Asterix) and calls for his help. Panoramix the druid makes a barrel of magic potion; Asterix and Obelix join Jolitorax into Britain for help.

After they arrive there, the road to the village appears not to be so smooth: the Romans have been warned and again and again, the three have to go into hiding, flee, or make detours. In the end, the Romans manage to destroy the barrel. All the same, Asterix, Obelix, and Jolitorax succeed in reaching the rebel village and repel the attack. Asterix, in a flare of genius and cunning, invents tea, which appears to give the Britons the strength

to permanently repel the Romans.

The Asterix stories are known for their great historic reliability. The creators have profoundly dived into literature from and about Antiquity (in particular Caesar himself and Strabo), which means the world as it stood in these days is represented fairly accurately – not considering the many conscious anachronisms. The background of this story, too, is accurate to a large extent. In the first century BC, Britain was inhabited by Celts, who did speak approximately the same language as the Gauls. In 54 BC, Caesar did undertake a penal expedition to the island, where he hit the forces of Cassivellaunos, who in the end had to surrender to Caesar.

One important thing is not accurate. In this album, Britain is depicted as a Roman province, complete with paved roads, a deeply-rooted garrison and a governor living in a palace. In fact, in Caesar’s days, Roman presence in Britain stopped with this expedition. Only a century later would (part of) Britain truly be incorporated into the Empire and would the Romans settle there permanently.

More than many other comics series, Asterix revolves around its humour. The humour, much of which consists of allusions to the present day, is probably an important reason behind the series’ universal appeal.

In many Asterix albums, other peoples are made fun of. As early as the third album, Astérix chez les Goths, the Goths appear as a militaristic tribe with Prussian Pickelhauben. Later on, the Hispanians, the Helvetians, and the Belgians get their turns, among others. Always the present peculiarities of these peoples are translated into Antiquity. The Spanish processions for the Holy Week, for example, resurface as marches of grimly-looking druids, and the Helvetians insist, with Swiss precision, that the floor is mopped immediately after a Roman orgy.

The slightly disparaging attitude towards other peoples seems typical of French chauvinism. In fact, however, both authors had a migratory background (Goscinny was descended from Eastern European Jews, Uderzo was born an Italian national). It is therefore not far-fetched to (also) view these stereotypes as a satire of French world view. No doubt, the authors themselves have often enough been confronted with unpleasant

prejudice.

No album makes such memorable, elaborate, and multi-faceted fun of a nation as Astérix chez les Bretons. Everything in Britain seems different from Gaul. From driving on the left to British cuisine, from row-huts to public ox carts with an added floor, nothing seems familiar. Even the Beatles (“four very popular bards” who have the girls yelling at them) and rugby (a violent game that Obelix is more than happy to take home to Gaul) are

depicted. The Londinium prison is a tower, and the palace of the governor strongly resembles Buckingham Palace.

In the 1960s, the time when this story was drawn, the cultural difference between France and the United Kindom was much bigger than it is today. A joke about pre-decimal money (page 16 strip 4) became outdated within five years, and even references to warm beer and proverbial Brittish self-containment seem dated today.

In the end, the book speaks very favourably of this strange country. In the mid 1960s, with the Second World War freshly remembered, no-one would have missed the parallels between Caesar’s expedition and the failed German invasion. To strengthen the parallel, the rebellious village is led by a chief called Zebigbos, a caricature of Winston Churchill. After their victory over the Romans, Asterix says: “À charge de revanche”. In other words: one day you may assist us on our own soil.

Translating a culture

When a story like this is translated into a language from the British Isles – be it English, Welsh, or Gaelic – this inevitable yields problems. Asterix is not an easy comic to translate in the first place, being as it is not only brimful of winks but also of puns. In the book, the British consistently use English idiom translated directly into French. In English, this will not be apparent, in Celtic languages not necesarrily. Various British customs, too, will not look as peculiar in the eyes of the English or the Welsh as they look in French eyes.

One way to deal with this problem is to fortify the original. As we shall see, the English translation has the Britons speak in a rather affected way. Another way is compensating a lost joke with a new or better joke elsewhere. We shall see that the Celtic languages make elaborate use of this device. Even though the story is about the Britons in general, the British culture caricatured in it is most of all South English culture. Some things, like rugby, are as popular among the Celtic nations as they are with the English; other customs, though, are English through and through. This enables the Celtic translators to make elaborate fun of the English, the big neighbouring people with their dominant culture and history of repression. As Alun Ceri Jones himself puts it: “We can be very scathing of the English in a way that the English translations can never be.”

The cultural, sometimes even political dimension of the translations is expressed in various ways. In the French original (page 5 strip 4), Obelix compliments Jolitorax for his trousers made of tweed, a Caledonian fabric. To Obelix’s question whether it is expensive, the Briton answers: Mon tailleur est riche. This is a reference to Assimil, a language method for self study which started in 1929 with English for French speakers. Millions of

French people began to learn English with this book. The first lessons begins: My taylor is rich. The method was apparently so successful that in 1965, the French associated the entire English language with it!

The translator into English decided to ignore this reference. Instead, he opted for: My taylor makes a good thing out of it. This sentence has an air of superiority. Yes, the fabric is expensive, but I don’t need to care: I can even afford a taylor! In Welsh, he says Dysglaid o ddŵr poeth a syrtgiad bach o fflefrith, os gweli di’n dda: (The British consistently pronounce ll as ffl; we will return to that later.) About the same, but even more affected. In Irish, the Briton insists on wearing treabhsar rather than bríste – a pun on briste (“broken”) but also a choice of vocabulary indication pretense.

In both Scottish translations – which by the way show a striking number of similarities – a political joke has been opted for. The tweed costs mair than their ile. They gie us that for free, the Scots translation has. A reference to North Sea oil, the profits of which benefit the state. In Gaelic, even the entire nation is for the Britons: Nas daoire na an dùthaich aca (“more expensive than their country”). The reference to Scottish oil resurfaces in both translations on page 10, strip 4, in a joke about a tunnel under the Mare Brittannicum (the Channel), which is due to be dug but will no doubt be delayed for some time.

If anything, the Scots and Scottish Gaelic translations are the two that are most overtly political. This is apparent even from the titles: wheras Welsh has Asterix a gorchest Prydain (“Britain’s vicatory”), Scots speaks of Asterix and the Sassenachs and Gaelic of Asterix agus na Sasannaich. (The Irish translation follows suit.) Sassanaich, literally “Saxons”, did not exist before the Germanic invasion in the fifth century AD. On top of that, this word is pejorative in Scots. The translators consciously use this anachronism so that it is clear from the very beginning who are made fun of in this story. (The Welsh translator opted for Brytaniaid here, literally meaning “British” but not as common as Brythoniaid. He did so as not have Welsh readers, who are after all Britons, too, and as speakers of a Brythonic language connected ever closer with the Britons of Antiquity, feel addressed.)

We may explain the prominent place for political jokes in the Scottish issues from the nature of Scottish identity. While in Wales, the emphasis is on cultural autonomy (including, of course, Welsh language), Scottish nationalism mainly has a political dimension – both translations were made around the time of the 2014 Scottish

independence referendum. The Scots translator was ready to affirm this when asked about the issue; he added that, should he have made the translation today, there would be no lack of Brexit jokes.

The political dimension is largely absent from the Irish translation. Unlike Wales and Scotland, Ireland is a sovereign state, and the translator saw no reason to change the original intention of Goscinny – mildly mocking a foreign land and its culture. For political jokes, he would have had to dive into history, and in his own words: “there aren’t many laughs in Anglo-Irish history.”

While the Welsh translation may be less explicit, it is definitely not devoid of politics. The allustions are more subtle; they often require a profound knowledge of the language. At a certain point, Asterix, Obelix, and Jolitorax (Inglansglorix in the Welsh translation, a reference to the match brand England’s Glory) go looking for the thief of their barrel of magic potion. When they break into the wrong house (page 29), they stumble upon an arch-English couple. The man is reading Les Temps (carved in a piece of marble) in a rocking-chair, and above the fireplace a plaque reading Foyer doux foyer can be seen.

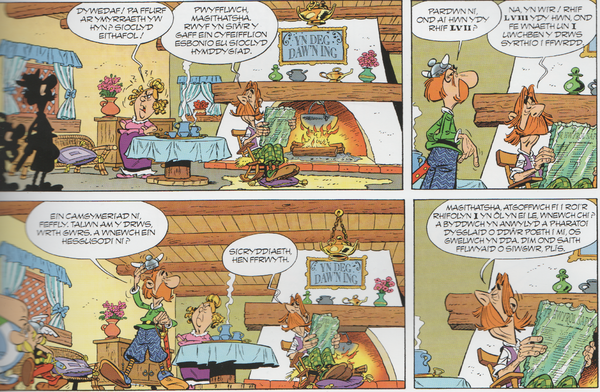

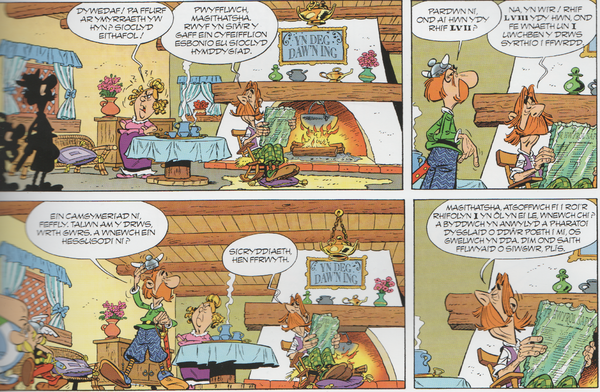

In the Welsh translation, the woman is called Magithatsha; the man’s name is Denix (after Denis Thatcher, Margareth’s husband). The text above the fireplace reads Yn deg daw’n ing. This is a double joke: the literal translation “our distress is pleasant” already hits hard, but reading the text aloud also yields “Yn Deg Downing” – Downing [Street] 10! The paper which the man reads in Welsh, by the way, is not The Times but Yr Hwyrol Safon – The Evening Standard, a very conservative London tabloid.

None of the other translations adapted this joke. Scots simply has Hame sweet hame, Gaelic has Mo dhachaigh (“my house/home”) and Irish, with Beannaigh an bothán, follows the English translation (which has Bless this hut). The paper the man reads in these three languages is the Telegraph.

There is no lack of references to the Second World War either. Just at the beginning (page 2 strip 1) we find a new reference. One of the two Britains who, with constrained horror, see the Roman fleet approach, says: “We shall fight them on the beaches.” This reference to Churchill’s “Blood, sweat, and tears” speech is absent from both the original and the English version. Here, however, it surfaces in three translations: beside the Welsh

version, the Scots and Scottish Gaelic translations employ this joke as well. The latter two add another wink. They have the other Britain say: “Who do you think you are kidding, mr. Caesar?” This is a reference to Dad’s army, a sitcom set in wartime Britain with the song “Who do you think you are kidding, mr. Hitler?” as an opening theme. For Britons, this joke is hard to miss indeed.

The fact that these translations have been made in the 2010s, rather than the 1960s, creates problems. The Beatles cameo is perfectly intelligible today, but no longer as funny as in 1966 when the band still existed. It also creates new possibilities, however. Jones told us that he explicitly tried to make the new translations children of their time. The reference to Margaret Thatcher – not yet prime minister at the time of the original but

neither at the time of the first Welsh translations from the 1970s – is one such possibility.

The joke about peculiar British money is, strangely enough, retained 40 years after Decimal Day, but the translator adds another element. He has Inglansglorix say: “Britain is not on the sesterce.” This allusion to the euro recurs in all other Celtic translations.

In addition all the jokes about the English, self-depreciation is not shunned. When Asterix and his friends order a cup of wine, (page 31 strip 2), the landlord says displeased: “One cup for the three of you? You must be Caledonians, what?” A reference, of course, to the stereotype of the thrifty Scots. Neither Scottish translation avoids this insult. Indeed, the Scots translation reinforces the joke by adding “Jocks” (an English slur against the

Scottish) as an explanatory footnote.

In Welsh, it is not the Scottish who have become the object of mockery. Here, the landlord’s question is: Ai rhai o’r Demetae sy’n gwerthu fflefrith o gwmpas y ddinas ydych chi? “Are you some of those Demetae who sell milk around the city?” The Demetae were a British tribe living in what is today Southwest Wales, in an area roughly corresponding to Ceredigion. For many years, the “Cardis”, the inhabitants of Ceredigion, went to London to sell their milk. But above all, in Wales they are known as people “who can buy something off a Jew, sell it to a Scot and still make a profit of it.” To be sure: the translator himself is from Ceredigion.

English: A ‘strange’ language?

An important part of the humour from the original concern the English language. On page 2, strip 1, it is said that the Britons had the same languages as the Gauls. As we have seen above, this approaches reality. “But”, the narrator adds, “[they] had a rather peculiar way of expressing themselves.” Then follows the picture, treated in detail above, where the two Britons see the Roman ships approach. One says: Bonté gracieuse! Ce spectacle est surprenant!, the other says: Il est, n’est-il pas? Anglicisms like these continue to pop up throughout the book. On top of that, Jolitorax and his compatriots consistently put the adjective before the noun. This syntactical difference appears to cause great wonder among the French. It even provokes a question in Obelix why Jolitorax is “talking in reverse”.

This is where the problems for the English translator begun. An English-language audience would not experience an expression like this spectacle is amazing or a tag sentence like it is, isn’t it? as really peculiar. The translator solved this problem by strongly fortifying these expressions. The Britons now speak a dated sort of upper class English: This is a jolly rum thing, eh, what? –I say, rather, old fruit! When the vessel of the three

rebels is hit by a catapult, Jolitorax’s complaint in the original is that it wasn’t franc jeu. Here, the English translator did not opt for fair play, but has Anticlimax say: I say, that’s not cricket! This expression was taken over by all Celtic translations, except for Scottish Gaelic.

The Celtic languages are not entirely free of this problem. Tag sentences like in English also occur in Welsh, and therefore wouldn’t make an impression in that language either. A joke about “shaking hands”, which for Obelix is an occasion to give Jolitorax a heavy shuddering (page 4, strip 3-4), must also be considered lost. (Even in Dutch, the anglicism de hand schudden largely displaced indigenous de hand drukken, let alone that it could still be understood the way Obelix does.)

The English language, however, shows more than enough differences from the Celtic languages. It seems to be the Welsh translation that makes most profound use of this. Here, too, the adjective precedes the noun (Irish and Scottisch Gaelic, where this would sound as strange, do not follow suit). Even more: the entire syntax is English, with the subject rather than the verb opening the sentence. Also, the Britons consistently pronounce ll as ffl. Since the sound [ɬ] is very hard to pronounce for non-Welshmen, realisations like this are frequently heard in beginning Welsh learners. Furthermore, the Britons often address each other with plural chwi – the English, after all, have long dropped their thou in favour of you, which originally was plural only.

Typical English expressions can be encountered everywhere. Often, the translator could simply follow the French original where his British colleague couldn’t. When Obelix is locked up in the “Tower” and his fellow prisoner thinks he has gone crazy (page 26, strip 2), in the original the latter says: “Il est devenu absolument noix.” The English translator resorted to a slightly affectated completely bonkers. In Jones’s Welsh translation, it remained hollol gnau, “completely nuts”. This didn’t stop him to think of new, much stronger examples such as joli dda sioe (“jolly good show”; page 3, strip 1) and rhosier ac afflan (“roger and out”; page 21, strip 1).

In the other language versions, such literal translations repeatedly occur as well. The first words the Britons utter on page 2 in the Irish version are Cór bladhmaí!, or cor-blimey in Irish spelling. Jokes about the English language, however, are not as prominent here as they are in the Welsh translation. This may be explained from the weaker position of their own language. Speakers of Scottish Gaelic and Irish so often have to make use of English in daily life that it is no longer a foreign language. The English language as such causes no more wonder. On top of that, we already established that Welsh identity, far more than Scottish or Irish identity, revolves around language.

The translator into Scots has used only a few English expressions in his version. Even though Obelix thinks Mixtermax (Jolitorax) has a funny accent (page 5, strip 1), the Britons, like all other characters, use typical Scots words like wee (page 2, strip 3), lassie (page 15, strip 4), and clachan (page 16, strip 3). The Britons are distinguished in this story, though, through their dialect: the translator has them speak the Edinburgh dialect, which is a form of Scots but sounds distinctly English in the ears of rural speakers. This can probably be explained from the linguistic position of Scots. Being a sister language to English, the translator must be careful with English idiom. Expressions like goodness gracious or cor-blimey would sound unnatural in Scots, but not as outlandish as they would in Welsh or Irish. This didn’t stop the translator to have the “Sassenachs” utter

an arch-English jolly every now and again, by the way.

Conclusions

The translations of Astérix chez les Bretons into various Celtic languages offer some unique opportunities, which stem from the intense contact the Celtic nations have had with the English through the centuries. The humour of puns and anachronisms inherent to Asterix is perfectly suitable for adding such allusions. Whereas the French original gapes at the strange customs of this neighbouring people, and the English translation essentially serves as a laughing mirror, the Celtic translations bear the traces of age-long political repression and cultural dominance. Here, we observe a difference between the Welsh translation and both Scottish translations. The first one intensively mocks the English language, while the latter two contain more political jokes. Such jokes can be explained from the various ways in which both Celtic nations usually express their identity.

Dalen Llyfrau can be called an artistic and publicitary success. Over the past thirteen years, they enriched the Celtic book market with numerous issues in a popular and easy reading medium, and they have succeeded in making these known to a wide audience. Although such a thing as a comic book can never save an entire language, this success does make one hopeful for the future.

The authors want to express their gratefulness to Alun Ceri Jones, owner of Dalen Llyfrau and translator into Welsh, for his patient and elaborate commentary to all aspects of his work. They also thank the other translators: Antain MacLochlainn (Irish), Matthew Fitt (Scots), and Raghnaid Sandilands (Scottish Gaelic). Without their assistance, the writing of this paper would not have been possible.

One Comment

Christian

Martine and Wouter, thank you for the insights!