A ’chomhachag bheag uaine ‒ Duolingo in Scottish Gaelic (and Irish, and Welsh)

The online learning platform Duolingo offers three courses in Celtic languages: Irish, Welsh and Scottish Gaelic.

Learning a language through Duolingo has been found to be effective in several studies, although there are a few downsides: the vocabulary is somewhat random, there is a lack of nuance in the explanation of the grammar, and the focus on ‘gamification’ makes it easy to score points without acquiring an active grasp of the material. Fortunately, on the individual level, these downsides can largely be addressed by means of taking an active approach to language learning. Moreover, Duolingo has done a lot for minority languages by both raising awareness of their existence and lowering the bar to start learning a new language.

A Dutch version of this article was published in Kelten 87.

When Duolingo announced it was adding a third Celtic language, this beta tester jumped at the chance. Because one of my special interests is learning (small) languages. A new language is like a door to a new world for me. Sometimes that door is only ajar, as with the Navajo course, but even then light shines through. Moreover, it is important to keep the small languages alive; they are vulnerable cultural assets in a fragmenting world.

Sadly, the last speaker of a language dies every other week – and with it, millennia of culture, condensed into the unique lexicon and grammar of that language. Celtic languages are also at risk. Take Scottish Gaelic, for example: last year research showed that only 11,000 people still use it actively. These are mainly the older islanders, in the Outer Hebrides of Scotland. It is expected that this year the percentage of speakers there will also drop below 50%, threatening the viability of the language. This is why I really like initiatives like Duolingo.

The Green Owl

For those not familiar with it; Duolingo (2012-present) – whose mascot is the little green owl Duo – is a (free) American app and website for learning languages with, based on collective intelligence. Currently, the system offers as many as 98 different language courses, among 38 languages. There are 35 courses from English, including French, Korean, Turkish and Welsh, as well as minor languages like Navajo and art languages like Klingon and High Valyrian. The three Celtic languages on offer were developed by enthusiastic users of the platform. Irish was the first Celtic language to appear on Duolingo, in 2014 (beta version). Welsh has been available since 2015 (also in beta) and three years later more than a million people had already signed up. After seeing the popularity of Irish and Welsh, a 28-year-old teacher of Scottish Gaelic became so enthusiastic that he spontaneously applied to host a Duolingo course in Scottish Gaelic. And with success, in eight months Ciaran Iòsaph MacAonghais developed the curriculum for the course. To do so, he recorded more than 7,000 audio clips from people who speak the language. The voices of MacAonghais’ uncle and grandmother, among others, appear in the lessons.

In a nutshell, the method works by taking multiple lessons within a language tree while developing knowledge and language skills along the way. The visual style of learning is integral to the method and the experience. Many of the lessons come with images and audio recordings, and there are “Tips”: detailed notes for each lesson explaining grammar concepts and vocabulary usage. There is also a forum where users can ask questions and interact.

Because of the many elements of gamification (Huynh et al. 2016), the app is quite addictive. Every day I get messages (emails and push notifications) from Duo, in which the little green owl urges me to study – “Got 5 minutes? Time for a tiny Scottish Gaelic lesson!”, “Your Irish lessons won’t take themselves!” and “Keep Duo happy!” – and he starts crying when I don’t get around to it for a day. The system itself has also gone to great lengths to give users a regular dopamine rush. For example, there are ‘lingots’: rewards that you can earn by completing lessons and with which you can buy all sorts of things, such as new clothes for little owl Duo. There is also a leaderboard, where you can see how you are doing compared to your friends, there are levels and XP (experience points), and there is a system of badges that are displayed on the user’s profile. But does such an approach work?

Effectiveness & Efficiency

Because Duolingo prides itself on being able to teach users a foreign language in just a few minutes a day, several studies have been conducted on its effectiveness (in the system from English). One of the first studies on the app comes from 2012 and focused on determining the effectiveness of Duolingo in helping users learn Spanish. The researchers conducted tests before and after the study and measured language improvement per hour of study (Vesselinov & Grego, 2012). It was found that Duolingo’s impact on language improvement was statistically significant. These results are confirmed by another study, which aimed to determine the effectiveness of the application by evaluating the listening and reading skill levels of beginner-level Spanish and French learners. That study found that most users achieved an intermediate level of reading comprehension and a beginning level of listening comprehension. Moreover, the scores of these users – in these two areas – were comparable to those of university students after four semesters of foreign language study (Jiang et al. 2020). Therefore, the study concluded that Duolingo is an effective and efficient app for language learning.

Bennani & Mosbah (2020) examined the effectiveness of Duolingo in helping language learners develop vocabulary and grammar acquisition. According to this study, the Duolingo platform has a great effect on vocabulary and grammar development, and therefore the researchers advocate integration into classrooms. A similar study was conducted by Pilar Munday (2016), who examined the Duolingo platform as part of the classroom experience. In this study, the language learning app is considered a supplementary learning tool in traditional high school level Spanish classes. In addition to the studies mentioned above, there are many other studies that focus on different aspects of the language learning platform. There are case studies that focus on the structure of the language courses offered (Huynh, Zuo & Iida, 2016), that look at reliability of Duolingo’s language tests (Ye, 2014) and other more general studies on the platform (such as Ahmed, 2016). Overall, Duolingo has been praised for its effectiveness in helping users acquire beginning to advanced foreign language knowledge.

So, full of enthusiasm, I began learning three modern Celtic languages – Scottish Gaelic, Irish and Welsh – through Duolingo. I installed the app on my phone and created a shortcut to the website in my browser. The combination of learning through those two different systems seemed ideal, but I soon noticed that there was a pitfall in that as well. In the beginning I was very serious about making time for each language in my agenda, to study from behind my computer, with a notebook next to it, but I noticed that I increasingly tried to score some points on the app in between, which gave me the feeling that I was already doing very well, without really putting much effort into it. And without me making any significant progress with the languages. This is also due to how the system responds. Because of the many elements of gamification, Duolingo often doesn’t really feel like studying to me, but more like a fun game on your mobile. And within that game, it’s pretty easy to score a lot of points without really learning anything. But of course, as a student, that’s up to you, and you can overcome this by planning your study sessions and taking notes on the material provided.

Duolingo’s power of repetition works well for me. What also helps for memorization is that there is a lot of humor in the app, both in the example sentences and in how the grammar is explained. Take the very first ‘Tip’ in the Scottish Gaelic course, for example, “The Gaelic alphabet contains 18 letters. This is the perfect amount of letters. Anything more would be frivolous and wasteful. There is no J, K, Q, V, W, X, Y, or Z. This is a major inconvenience during games of Gaelic Scrabble, but otherwise presents no difficulty.” (And since then, I’ve been feeling really keen on playing Gaelic Scrabble.) I really enjoy playing with the little green owl like this, and I’m definitely learning a lot of vocabulary from it. The diversity in the example sentences is heartening – there are many same-sex couples, for example, and even phrases like “I am usually a man, but sometimes I am a woman” and “no pride for some of us without liberation for all of us” come by.

An added bonus of Duolingo is that you can check out the other languages just for fun. While waiting in line at the supermarket, I did some Arabic and Hebrew lessons. And because the lessons in the Celtic languages were still so fresh in my mind, I suddenly noticed all kinds of funny similarities between these totally separate language families. The VSO word order, for example, and the broader use of “and” (in cases where I would use “while” or “when”). The lack of indefinite articles while definite articles do exist. And the inflected prepositions used to express possessions and obligations. With Owl Duo, I became more aware of Celtic grammar, even though I wasn’t even working on a Celtic language.

Still, there are three downsides to be considered if your goal is to really master the language.

Downsides

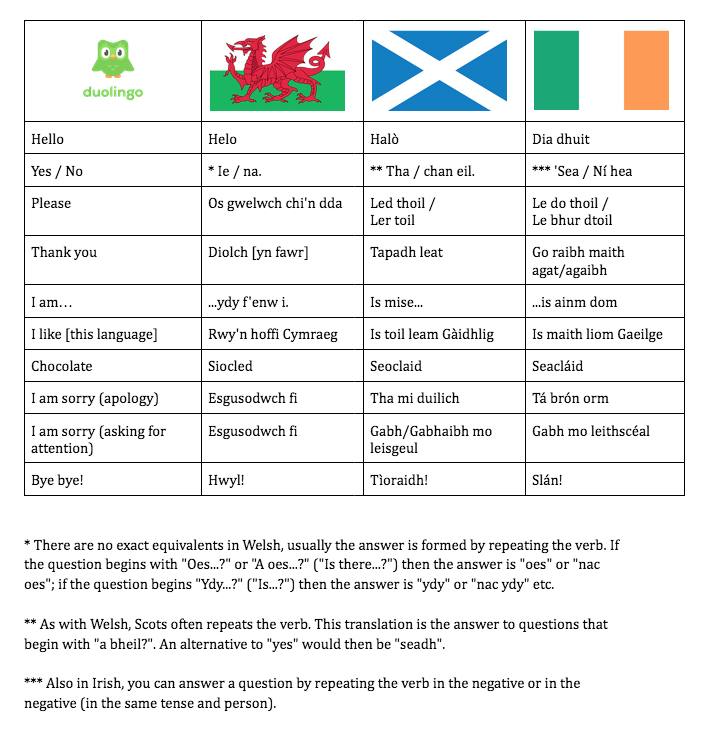

First, I found it irritating that the vocabulary seems to be chosen rather randomly. Because the courses are developed by different teams, there is quite a bit of difference in both content and level. The first words you encounter in the Scottish Gaelic course are “dog”, “pig” and “girl”. Welsh begins more practically with hello (helo), good morning (bore da), good afternoon (prynhawn da) and good evening (nos da). With Irish, you learn man/woman (fear/bean), girl/boy (cailín/buachaill), and (agus) and the construction for the verb ‘to be’ (is, e.g. “I am…” becomes “is…mé”) in the first lesson.

A second flaw I find is that you miss all the nuances and contexts. For example in Welsh, if you have to give a translation of “I like” there, the system calculates both “Rwy’n hoffi” and “Dw i’n hoffi” correctly, but nowhere is it explained whether there is a difference between these two expressions and if so, what that difference is. There is sometimes something explained about formal and informal constructions, but not how formal that formal is then and when you might use which form. And I don’t want to just assume that it will be the same as in Dutch, because I know that in German, for example, it is slightly different than in Dutch.

A third point is related to gamification, which makes it easy to score without real knowledge: the app confirms me in my strong point – written translation, with or without a dictionary or list. My speaking and writing skills lag behind, because the app doesn’t challenge me enough to really memorize things properly. So there too, as a student, you have to take responsibility for your own learning process: set goals, put appointments in your calendar and test yourself outside of the app.

As with the temptations of gamification, these three points are easily overcome by an active learning attitude. Especially if you are using Duolingo as a supplement to another learning method, you can have a lot of fun with it and get serious returns. In addition to the official systems, there is also a large community of Duolingo users who help each other, for example through challenges on Twitter and additional word lists on Memrise. Finally, I have to honestly confess that I don’t know if I would recommend it to anyone to learn these three Celtic languages interchangeably, as I do now. It’s fun to see how the different courses work in terms of lesson structure and interesting to compare grammars, but not so practical if you want to remember how to spell “chocolate”!

The language communities

Duolingo is having a significant effect on Celtic languages and language communities. The Internet is full of heartwarming stories of how young people can now suddenly talk to their grandparents in the Celtic (or, in the case of Navajo, for example, the Native American) language of their youth. The statistics don’t lie either – Scottish Gaelic quickly became the fastest growing course on the platform; where before this initiative there were less than 100,000 speakers of the language worldwide (at various levels), by January 2021 there are already more than 486,000 people active in the Duolingo Scottish Gaelic course.

Of course, not all of these people will suddenly become fluent in Scottish Gaelic – starting a course is a lot easier than completing one. Still, these large numbers help the small languages tremendously by generating positive attention. There is still far too much denigration and talk about minority languages (“worthless”, “useless”, etc.) and I think Duolingo can do something to counter that negativity, by adding a little prestige.

In addition, Duolingo lowers the threshold to start (and continue) learning a small language. After all, one of the biggest problems with that is always the lack of resources, support and community spirit. Duolingo manages to bring those things together on an easy to access and use website. The rest is then up to us, the users, who together can help an endangered language not be forgotten.

Bibliography

- Ahmed, Heba Bahjet Essa, “Duolingo as a bilingual learning app: a case study”, Arab world English journal 7 (2016) 255-267.

- Bennani, Walid en Rafik Mosbah, “Investigating the effectiveness of the Duolingo platform in developing learners’ vocabulary and grammar acquisition: the case of CEIL adult beginner EFL learners”, Trans 22 (2020).

- Huynh, Duy, Long Zuo en Hiroyuki Iida, “Analyzing gamification of “Duolingo” with focus on its course structure”, in Bottino, Rosa, Johan Jeuring en Remco Veltkamp (red.), Games and learning alliance, Lecture notes in computer science 10056 (Utrecht 2016) 268-277.

- Jiang, Xiangying, Joseph Rollinson, Luke Plonsky en Bozena Pajak, Duolingo efficacy study: beginning-level courses equivalent to four university semesters (2020).

- Munday, Pilar, “The case for using Duolingo as part of the language classroom experience”, Revista Iberoamericana de educación a distancia 19 (2016) 83-101.

- Vesselinov, Roumen en John Grego, Duolingo effectiveness study (2012).

- Ye, Feifei, Validity, reliability, and concordance of the Duolingo English test (2014).

Leave a Reply