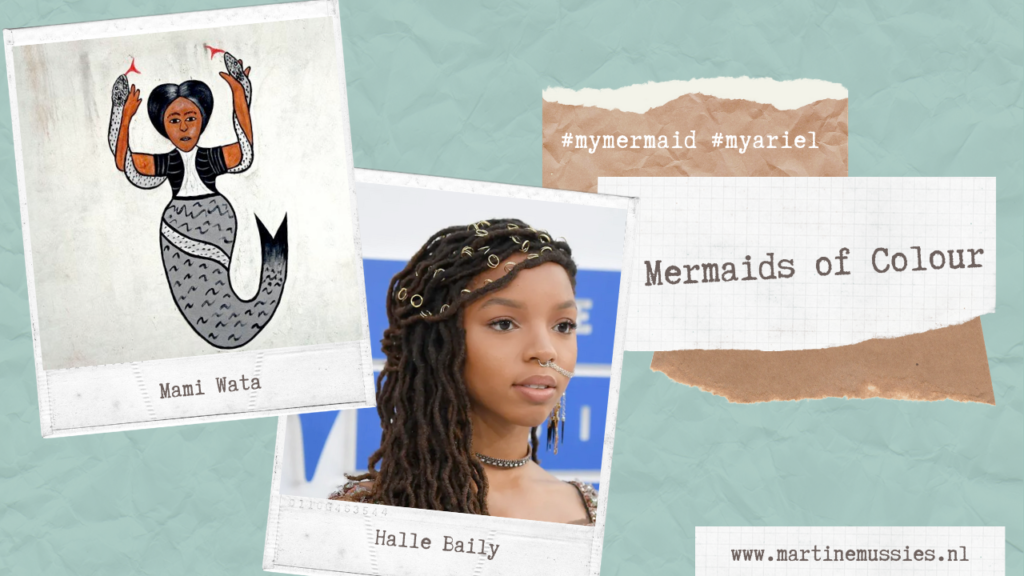

Mermaids of Colour

When the Disney studios announced that they had cast Halle Bailey in the role of Ariel, aka The Little Mermaid, for their latest live-action remake, there was a wave of reactions and most of all: criticism. Twitter hashtags #NotMyMermaid and #NotMyAriel became trending topics and Halle was ridiculed in words as well as in ‘anti-fan art’. And why? Not because anyone doubted the acting and singing talent of the 19-year-old R&B star. Nobody questioned the judgment of director Rob Marshall who praises Halle’s ”rare combination of spirit, heart, youth, innocence, and substance, plus a glorious singing voice”. No, the hatred is based solely on Halle’s skin colour supposedly not matching the role. In my opinion, this online hatred of the new mermaid isn’t just racism based on white privilege, it’s rooted in whitewashing.

This blog post combines some of my earlier writings on this topic, such as this article for Lover and this blog post for Geek Girl Authority.

Whitewashing, a casting practice in the film industry in which white actors are cast in non-white roles, is one of Hollywood’s worst habits. Sometimes, a movie employs blackface (and/or ridiculously exaggerated speech and body language), but luckily this is very rare nowadays. More often, black characters are whitewashed entirely, erasing the representation of characters of color. This might seem a habit of the past, but sadly, it isn’t. Think about Angelina Jolie as Cleopatra, for example. And in Rounders and Argo, the (respectively) Asian and Latinx characters are played by white actors. The movie Stonewall is about the Stonewall riots and focuses on a fictional white protagonist instead of on Sylvia Rivera and Marsha P. Johnson, or some of the still living trans lesbians of colour like Stormé Delarverie or Miss Major Griffin-Gracy. But this practice is also in use for fictional characters. For example: Scarlett Johansson in the remake of Ghost in the Shell. Emma Stone in Aloha. The entire casting of the Avatar: the Last Airbender movie. And the Prince of Persia, based on the hit series of video games, casted Jake Gyllenhaal as the Prince. As Amanda Scherker (2014) noted, in this film, “[n]one of the main actors were of Iranian, Middle Eastern or Muslim descent.”

You might think that, since the mermaid is a fictional creature, she could just as easily be green or blue as black, brown or white. But if you look at the history of the mermaid, you will see countless black and brown mermaids, who were there much earlier than their white sisters. Hans Christian Andersen actually wrote his Little Mermaid as a gay romantic love letter, wrapped in a fairy tale; Disney remediated it into a (blatantly patriarchal) movie thirty years ago (Mussies 2016). Neglecting centuries of mermaid history from Africa and the Caribbean, for Disney whiteness was and still is the default. And although, for some of their fans whiteness might be the preferable option, I am happy with the casting of a black woman as Ariel. Maybe she is not your Ariel – well, my “Poor, Unfortunate Souls”, then you’ve had yours! Now is the time when mermaids claim agency, for example in online fan art, such as the Monstrous Mermaids (Frankenstein Mermaids, Zombie Mermaids, Vampire Mermaids and Robot Mermaids). We need powerful mermaids who represent all of us – the mad mermaids, the fat mermaids, the trans* mermaids, the mermaids with disabilities and the mermaids of colour.

Black & brown mermaids

Black and brown mermaids have been around long before Hans Andersen’s creation of The Little Mermaid and certainly long before Disney. These mermaids have existed in folklore and art, passed down from one generation to the other by word of mouth. Conceivably, multiple cultures throughout the world have stories about mermaids in their spirituality and mythology. Cultures where mermaids are goddesses and creators tend to be largely African, Polynesian, Native Hawaiian and indigenous African cultures (Baptiste, 2019). In these cultures, mermaids are portrayed as sirens, water spirits and water elementals among other unique portrayals. For example; Yemaya and Mami Wata are the most prominent water elementals in African and Caribbean folklore (Drewal, 2008). Yemaya is believed to be the mother of all living beings and is worshipped in West Africa among the Yoruba and in the Caribbean (Dorsey, 2019). Mami Wata is the pantheon of water spirits in African and Caribbean folklore. She is often shown as an ancient goddess with both womanly and fish features.

African Mermaids

As my Kenyan friend Triza explained to me, in African cultural tradition, word is bond. The wisdom, culture and history of African communities are passed down from generation to generation by word of mouth. Oral literature, as represented by folklore, fables, myths and creation stories, is one of the most salient features of African tradition. The stories told by grandparents to grandchildren, by the fireplace each evening, map the beginning of African culture and origin. As such, the history and culture of African people can scarcely be uncovered in fossils or excavations; rather, these things are wholesomely found in the stories told by African people and the stories passed on to younger generations. Notably, merbeings and water spirits have always been an important part of African oral literature (Drewal, 2008). Depictions of merbeings vary from beautiful maidens with long hair and fish tails, to shy and reclusive creatures only fleetingly seen, to ape-like beasts and other traditions. Dispositions of these creatures range from protectors of the sea, to water spirits, to seductive sirens. On the whole, merbeings have existed in African legends, myth and folklore for centuries.

As mentioned above, perhaps the most popular water spirit in African oral literature is Mami Wata. While popularly known as a water spirit, various West African communities call her a mermaid. Mami Wata is depicted in West African lore in its primordial aspects as a mermaid, half-fish or half-reptile. The most common portrayal of the water spirit is a woman with long flowing hair, enviable beauty and snakes around her neck (Paquette, 2019). She is ascribed transformative qualities whereby it is believed that Mami Wata can take on any form− snake, fish or human. Creation myths − such as Dogon creation myths − dating back to 4000 years ago, recognize the existence of Mami Wata. Mesopotamians called the water goddess Mami Aruru. Ancient African folklore associated Mami Wata with the Egyptian deity Isis; the mother of Horus and daughter of Ra (Brown, 2016). The African deity has found homage largely across West Africa and partially across Eastern Africa where she is referred to as Mamba Munti. It is important to note that Africans perceive water spirits and merbeings not simply as mythological creatures but as spiritual ones (Johnson, 2018). As such, there are many cultures which worship the deity in question. Moreover, there exists a matriarchal priesthood dedicated to the worship of Mami Wata and related deities.

Black mermaids

Southern Africa, like many other regions, has a rich tradition of mermaids, mermen and other water spirits, who are often depicted as having black skin. . In Zimbabwe, mermaids and water spirits are referred to as Mondao (Swancer, 2017). Zimbabwean folk lore portrays merbeings as malicious creatures that enjoy pulling fishermen and swimmers under the sea to their death. Zambians have the legend of Nyami Nyami− a dragon-like creature with the head of a fish and a body of a snake− a water spirit believed to control the life in and around Zambezi River, as well as protect and sustain Tsonga people. Kitapo, the river mermaid, is also famous among the people of Zambia. Folk lore has it that the river mermaid demands offerings and takes human sacrifices from the inhabitants on the banks of Zambezi River. She is also known to protect children from rapids and punish criminals. Merbeings believed to exist in Zambezi River and Victoria Falls are celebrated in an ancient ritual of the Lozi people known as Kuomboka ceremony.

South Africa also has rich folk lore and tales about merbeings which have existed for centuries. These beings are commonly referred to as Kaaiman, and are typically described as half-fish women black hair and red glowing eyes. Like many mythological water creatures in African folk lore, these beings are perceived as powerful spiritual beings and are known to lure travellers to the water to drown them (Drewel, 2008). These creatures are popularly found in African oral literature. Additionally, these are ancient rock paintings of humanoids that resembled mermaids that have been discovered in arid areas of Karoo (Swancer, 2017). These paintings, believably painted by the Khoisan people of the region, speak mystery especially because it is difficult to ascertain why desert dwelling people like the Khoisan would have mermaids as part of their lore.

On the whole, mermaids, mermen and fish-tailed mythological creatures are an important part of African tradition. These creatures have existed in African folklore and tales for centuries. Some of the most popular merbeings include Mami Wata, Kitapo and Kaaiman. Merbeings are not only perceived to be mythical creatures but also powerful spiritual beings. As such, they are revered in African culture with some, such as Mami Wata, being worshipped as deities. It is important to note that most knowledge of merbeings within the African continent is drawn from oral narratives − myths, tales and folklore.

Brown mermaids

Mermaid lore has an equally long history in Asian countries such as Japan, India and China, in which their skin colour is often brown. Notably, there is an Indian mermaid princess called Suvannamaccha who appears frequently in Thai and Southeast Asian versions of mermaid lore. The figure of Suvannamaccha is very popular in Thai folklore as in houses and shops throughout Thailand because it is considered to be a good luck charm (Sastri, 2007). The story of the mermaid Suvannamaccha centers on her encounter with Hanuman, one of the major devotees of the deity Rama. According to this story, the mermaid princess meets and falls in love with Hanumann while he attempted to enable the rescue of Rama’s wife and she was on a mission to destroy this mission (Lutgendorf, 2007). Generally, Suvannamaccha is portrayed as a golden mermaid or a golden fish and is a critical part of Asian mermaid lore.

On the whole, the existence of black and brown mermaids in oral literature and folklore thwarts the inaccurate belief that mermaids should be exclusively white or pale-skinned (Roffey, 2020). Despite the most popularized depiction of a mermaid as Ariel from the animated version of The Little Mermaid, with red hair and pale skin, there are many cultural narratives that point towards the notion that black and brown mermaids have been in existence for a very long time.

#MyMermaid #MyAriel

That’s why it’s great to make the new Little Mermaid a mermaid of colour. The #NotMyAriel and #NotMyMermaid people’s argument that it is the same as having princess Tiana played by a white man is literally drawn out of proportion and out of context, as princess Tiana is the only black princess in the entire Disney franchise. Besides this single black princess (Tiana from The Princess and the Frog), there is a single Asian princess (Mulan), a single Pacific Islander princess (Moana) and a single Middle-Eastern princess (Yasmin from Aladdin). We have the very problematic story of Pocahontas (more about that in another article) and for the rest, there are many, many, many European princesses, who are all as white as snow. Who should black girls identify with?

As their history proves, mermaids can be anything they want, in all the colors of the rainbow. Claiming that Ariel should necessarily be white is ridiculous, and it’s no less than appropriate for Disney to stop whitewashing and their main characters to become a reflection of their audience, with more diversity. The beginning is there, because Disney can set the record straight with their live-action remakes: Naomi Scott played Princess Jasmine and Liu Yifei will play Mulan. Now is the moment for Ariel to escape her mold and to honour her roots, as a Black Mermaid. And I am looking forward to see the powerful, young and talented Halle Bailey shine as Ariel in The Little Mermaid.

Fan Art

As I think that we should support all our mersisters, I am very happy with the casting of a black mermaid. And I am not the only one who feels this way. Against the backlash, artists – amateur and professional alike – were inspired by Disney´s decision and shared some quite magical images of Halle as Ariel on their social media. I made a selection of this beautiful black mermaid fanart, to show that Halle – just like other Geek Girls – can be anything she desires.

(in random order and just google for more eye candy)

Alice X. Zhang is a professional illustrator for Marvel and she painted this stunning work of art featuring Halle as Ariel, swimming, with red hair and a green tail.

Another Marvel illustrator – and the author of the comic Blackbird – who drew a redhead Halle mermaid is Jen Bartel. She also added pearl ear studs and the beautiful sea flower that all Ariel fans know and love.

Instagram artist Lady Nefertitii drew Halle with dreads or braids, in the famous dinglehopper scene. Super funny!

While Instagram artist Kaiayame choose for Halle to wear the well known (and controversial) pink princess dress. I love it!

American storyboard artist Nilah Magruder shared her vision on a black Ariel with this perfect comic book like drawing of the `Part of Your World` scene, that even includes a realistic looking Flounder.

And how about this adorably cute Halle mermaid drawn by Twitter artist Ivy (@Ivykaelinart)… isn´t she just wonderful?

Fan art, like the examples above, make me even more excited about the new Little Mermaid live action movie. I am certain that Halle Bailey will do an amazing job. Oh and I am very curious who will play Ursula… 😉

References

Baptiste, T. (2019). Mermaids Have Always Been Black. New York Times. Retrieved from: https://www.nytimes.com/2019/07/10/opinion/black-little-mermaid.html

Brown, E. (2016). The Black Mermaid: ‘Just because we’re Magic, Does Not Mean We’re Not Real’. Let Them Flourish. Retrieved from: https://www.letthemflourish.com/blog/2016/blackmermaidsarereal

Drewal, H. (Summer 2008). “Mami Wata: Arts for Water Spirits in Africa and Its Diasporas”. African Arts 41(2): 60-83. Retrieved from: https://doi.org/10.1162/afar.2008.41.2.60

Dorsey, D. (2019). Mermaids Can Be Black And International Folklore Proves It. Travel Noire. Retrieved from: https://travelnoire.com/black-mermaids-international-folklore

Drewel, H.J. (2008). “Introduction: Charting the Voyage”. In Sacred Waters: Arts for Mami Wata and other divinities in Africa and the diaspora. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Johnson, E.O. (2018). Mami Wata, the most celebrated mermaid-like deity from Africa who crossed over to the West. Face 2 Face Africa. Retrieved from: https://face2faceafrica.com/article/mami-wata-the-most-celebrated-mermaid-like-deity-from-africa-who-crossed-over-to-the-west

Lutgendorf, P. (2007). Hanuman’s Tale: The Messages of a Divine Monkey. Oxford University Press.

Mussies, Martine. (2016). ‘The Bisexual Mermaid: Andersen’s fairy tale as an

allegory of the bi-romantic sexual outsider’, EuroBiCon Conference. Amsterdam, July 28th to 31th, 2016. University of Amsterdam.

Paquette, D. (2019). Africa celebrated black mermaids long before Disney and #NotMyAriel. The Washington Post. Retrieved from: https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/africa/notmyariel-african-mermaids-existed-long-before-disney/2019/07/09/25efe4b6-a23f-11e9-b7b4-95e30869bd15_story.html

Roffey, M. (2020). #Notmymermaid: the Disney row is ridiculous – who knows what mermaids look like? The Guardian. Retrieved from: https://www.theguardian.com/books/2020/mar/16/disney-notmymermaid-row-ridiculous

Sastri, S. (2006). Discovery of Sanskrit Treasures: Epics and Puranas. Yash Publications.

Scherker, Amanda. 2014. Whitewashing Was One Of Hollywood’s Worst Habits. So Why Is It Still Happening? . Huffpost. Retrieved from:

https://www.huffpost.com/entry/hollywood-whitewashing_n_5515919

Swancer, B. (2017). The Evil Mermaids of Africa. Mysterious Universe. Retrieved from: https://mysteriousuniverse.org/2017/03/the-evil-mermaids-of-africa/

with many thanks to Tim de Visser for his help!

THANK YOU! Thank you for sharing this! People want to say it’s because she doesn’t have red hair but it’s literally a movie that has the tools and abilities to make her have red hair. I, as a young black woman, don’t see enough black representation in the movie industry! And if there are roles for black people we are oppressed, stereotyped and we just don’t get enough original story lines. Thank you for sharing this. You did not stutter.