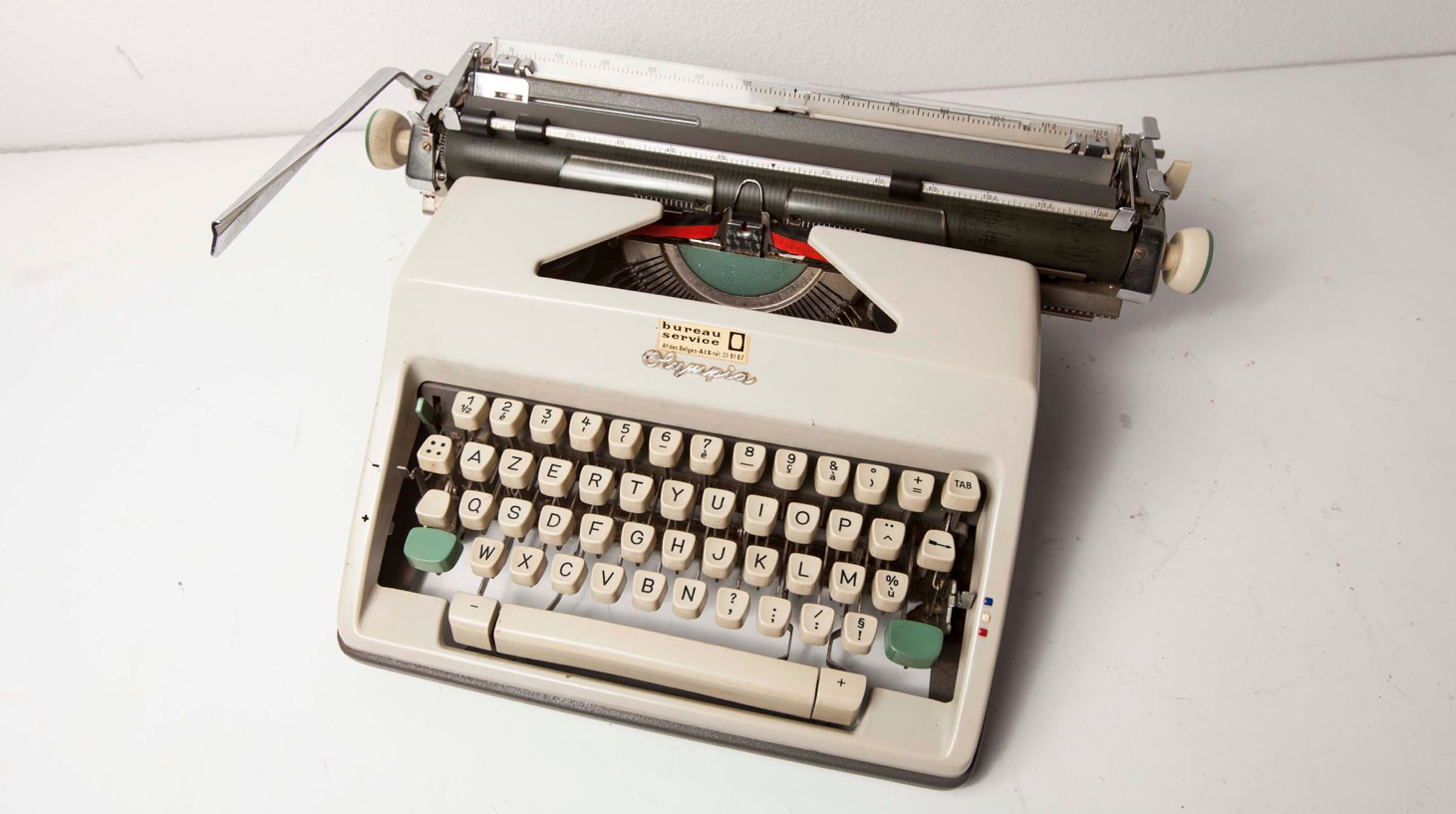

Last week, I got a nice brooche – or fibula, if you like – from the British Library. It is an enamel pin of an old fashioned typewriter, the kind of machine that’s also featured in the sidebar of this weblog. I like typewriters a lot, but not just because of my love for writing, my fascination for retro technologies, the funny scenes in the movie The Secretary and the memory of playing Leroy Anderson’s 1953 piece with our youth orchestra. No – for me, the typewriter is also a symbol of the emancipation of the writing and publishing woman.

Designed by Craig Yamey for the Writing: Making Your Mark exhibition range.

Since the development of printing, women’s crafts have developed. Long before the movable type, there was a robust custom of women creating scripts in western European episcopal centers. For example in the Convent of San Jacopo di Ripoli in Florence, in 1476, where girls and women put in a lot of effort into printing (Roper, 2017). This was not exceptional, young women were frequently trained by their parents or spouses to support printing businesses (Tusan, 2004). And that is a good thing, for – believe it or not – typing improves your thinking.

Twenty years ago, educational scholar Carol Christensen (1999) tried out this hypothesis with 35 low-scoring high-school students in Australia (who were probably around the same age as the girls in Convent in Florence). Her conclusion was that:

by facilitating students’ ability to put letters and words on the page, they increased their ability to produce text that was creative and original, more technically accurate, more logically sequenced and better organized and showed greater pragmatic awareness and sensitivity to audience […] These differences were not trivial.

Christensen (1999)

And Michael Russell (2002) compared two groups of school children who had to work out an essay in 45 minutes. One group had to write it by hand, one group could type it out. Not only did the typing kids hand in longer essays (which was to be expected), but also did they use better English (probably due to word recognition) and they developed their topics much more comprehensively. According to Russell, the children who typed the fastest had the highest scores of their class.

(Of course, these effects are not limited to the old fashioned typewriter, among others, the Dutch scholars Marjolijn van Weerdenburg, Mariëtte Tesselhof and Henny van der Meijden have already reported similarly positive effects of a touch‐typing course on the spelling and narrative‐writing skills on the computer of elementary school students. But that’s beside my point.)

Since the development of the typewriter, many women have benefit from this magical machine. Conferring to De Grazia (2017), a woman’s typographical union in France with a periodical entitled La Compositrice, and the first journal written by a lady, Godey’s Lady’s Book, were both printed in Philadelphia by Sarah Josepha Buell Hale (Brooks, 2017). Apart from that, in 1853, women were hired in the Day Book office in New York to write using typewriters and run a printing business (Roper, 2017).

Moreover, in 1857, Emily Faithful decided to set up her own printing company in Edinburgh, engaging women only (Tusan, 2004). In 1859 she created the Victoria Press and – saillant detail – hired men to do the hefty work (Stein, 2017). Giving to Brooks (2017), in 1863, Lisle Lester turns out to be the manager of the Pacific Monthly and fostered constructive engagements for inclusivity in the development of printing. Another lady, Emily Pitts Stevens, gained fame when she changed the Sunday Evening Mercury into the leading voice for suffrage (De Grazia, 2017). Stevens hired only women to set type for the paper (Stein, 2017).

A contemporary account of typewriters from Encyclopedia Britannica insisted:

Doubtless the novice who is learning the keyboard finds a natural satisfaction in being able to see at a glance that he has struck the key he was aiming at, but to the practical operator it is not a matter of great moment whether the writing is always in view or whether it is only to be seen by moving the carriage, for he should little need to test the accuracy of his performance by constant inspection as the piano player needs to look at the notes to discover whether he has struck the right one.

But the novice might as well be a “she”, for in the eighteenth and nineteenth century, there were different methods used to advertise typewriters especially for women. And it were women who engaged in the typeset their work as well. Many of the advertisements were done using posters made by unions (that consisted of both males and females), but apart from these, feminine printing companies such as Glogowski & Co. in Germany and Remington Typewriters in New York advertised themselves specifically targeting at women (Curtin, 2018). These posters were manuscripts that women type set to encourage others to join the trade. And implicitly: to find a new, mechanical, way into the art of expressing themselves.

References:

Brooks, D. A. (Ed.). (2017). Printing and parenting in early modern England. Routledge.

Curtin, J. (2018). Women and trade unions: A comparative perspective. Routledge.

Christensen, C. A. (2004). Relationship between orthographic‐motor integration and computer use for the production of creative and well‐structured written text. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 74, 551– 564. https://doi.org/10.1348/0007099042376373

De Grazia, M. (2017). Imprints: Shakespeare, Gutenberg, and Descartes. In Printing and Parenting in Early Modern England. Routledge.

Roper, A. (2017). The culture of music printing in sixteenth-century Augsburg (Doctoral dissertation, University of St Andrews).

Jones, D., & Christensen, C. A. (1999). Relationship between automaticity in handwriting and students’ ability to generate written text. Journal of Educational Psychology, 91(1), 44-49. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.91.1.44

Russell, M., & Plati, T. (2002). Does it matter with what I write? Comparing performance on paper, computer and portable writing devices. In Current Issues in Education [On-line], 5 (4). http://cie.ed.asu.edu/volume5/number4/

Stein, J. A. (2017). (Re) Making spaces and ‘working out ways’: Women in the printing industry. In Hot metal. Manchester University Press.

Tusan, M. E. (2004). Performing work: Gender, class, and the printing trade in Victorian Britain. Journal of Women’s History, 16(1).

Weerdenburg, M, Tesselhof, M, Meijden, H. (2019). Touch‐typing for better spelling and narrative‐writing skills on the computer. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 35: 143– 152. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcal.12323

That’s so interesting! I had no idea about the history. I remember learning to type on a typewriter as a kid. There’s something magical about it!