King Alfred & Canterbury

Of course I had heard some tales about Canterbury – a pilgrimage site in the Middle Ages, surrounded by Ancient walls (originally built by the Romans), that encircle its medieval center of cobbled streets and timber-framed houses. But I had never been there – until last summer. My stay in Canterbury allowed me to connect to the Alfredian world in a new way. This blog post is a reflection of my findings and the second of a series of four.

(April 2020 update: I also wrote a more “touristy” travel blog about Canterbury, which you can read here)

After singing in Rochester Cathedral and looking for Alfred’s connections to Rochester, I travelled South-East and sang praise in the so-called “capital of English Christianity” – Canterbury Cathedral. But Canterbury is more than a city with a stunning cathedral, it’s also a place with a chequered past, of holiness, murder, and colourful story telling. With this writing, I add a layer to the latter by thinking about King Alfred’s connections to Canterbury.

After the death of King Æthelred, Alfred took over the position of leadership amidst attacks by the Vikings. Markedly, after the 865 invasions and conquest of two Anglo-Saxon kingdoms – North Umbria and Mercia- by the Great Armey or the mycel heathen the assailants began to head south (Birth, 2018). Thus, the Kingdom of Kent was at risk. Nonetheless, in 878, coming in the defense for Canterbury, the king won the Battle of Edington and negotiated a treaty in 886 (Richards, 2015). As such in Canterbury, Alfred advocated for impartiality and command, recognized code of decrees, and a changed town.

For the Canterbury church, Alfred inclined to support leaders like Plegmund from his appointment as Archbishop of Canterbury in 890 (Pratt, 2007). Plegmund’s election to the Archbishopric of Canterbury is recorded in Manuscript E of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle: “Here Archbishop Plegmund was elected by God and all the people.” Apart from that, between 891 and 897, owing to spread the importance of Latin in Canterbury and other South Eastern settings, the king divided the importance of education and took part in the translation of accounts from Latin to Anglo-Saxon (Campbell, 2017).

According to the 19th century historian G. F. Maclear (1888), one of the most important religious houses of Alfred’s time was in Canterbury. St Augustine’s Abbey was, in Maclear’s words, a “missionary school” where “classical knowledge and English learning flourished.” Although there is no tangible evidence of the presence of Alfredian writings, there is much in the Abbey that resonates with him. St Augustine’s was in fact a Benedictine monastery, founded in 598 and in function as a monastery until its dissolution in 1538 during the English Reformation. Over time, St Augustine’s Abbey acquired an extensive library that included both religious and secular holdings. In addition, it had a scriptorium for producing manuscripts (Roebuck 1997).

Rendering to records from the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, in 873, the bishop of Canterbury sold land at Ileden, Kent for 25 gold coins, at Alfred’s will (Adams, 2018). Nonetheless, in Stowe Charter 19 – an 873 grant of King Alfred and Æthelred of Canterbury to Liaba – actions omitted in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle show that land was already under sale in the region. Surprisingly, this charter correspondingly seems to bolster the argument of Richards (2015) that Latin in Canterbury was on the decline. Similarly, as Pratt (2007) posits, that could have well been the reason for King Alfred’s stress on education in Canterbury, and Kent. Nevertheless, as in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle and the Stowe Charter 19, Canterbury land was sold during Æthelred’s and the community at Christ Church’s reign (Reuter, 2017). As a result, after the rocky start to his control, Alfred prospered winning key battles and securing territories.

My fantasies of walking through the fields were King Alfred once could have walked got a new dimension at the Medieval Studies Day in Antwerp (Belgium), last week. There I presented my #KingAlfred project and felt very inspired by the other talks, especially those by dr. Marianne Ritsema van Eck (on the holy land in observant Franciscan texts), by Merel de Bruin (on citizenship discourses in late antique preaching) and by professor Susan Oosthuizen (on the early medieval fenland landscape).

What struck me most from professor Oosthuizen’s paper, is her explanation of the groups of people Bede wrote about, who came to inhibit the Fenlands, “some with some Brittonic territorial names and others with names based on Old English elements” (Oosthuizen 2016). According to Oosthuizen, the people who named the places she focussed on were probably descendants of Romano-British people and may have been bilingual – 400 years before King Alfred’s educational program.

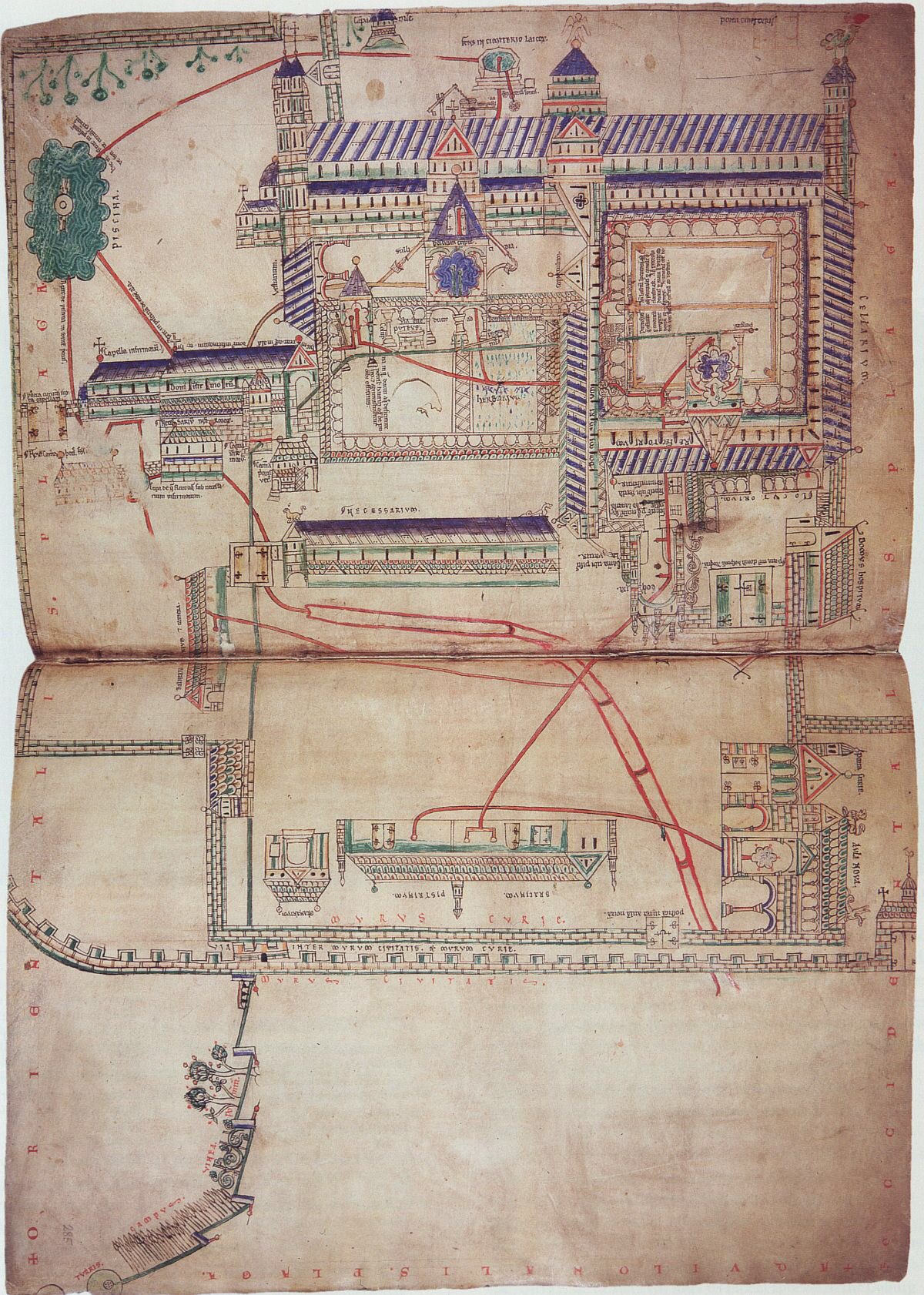

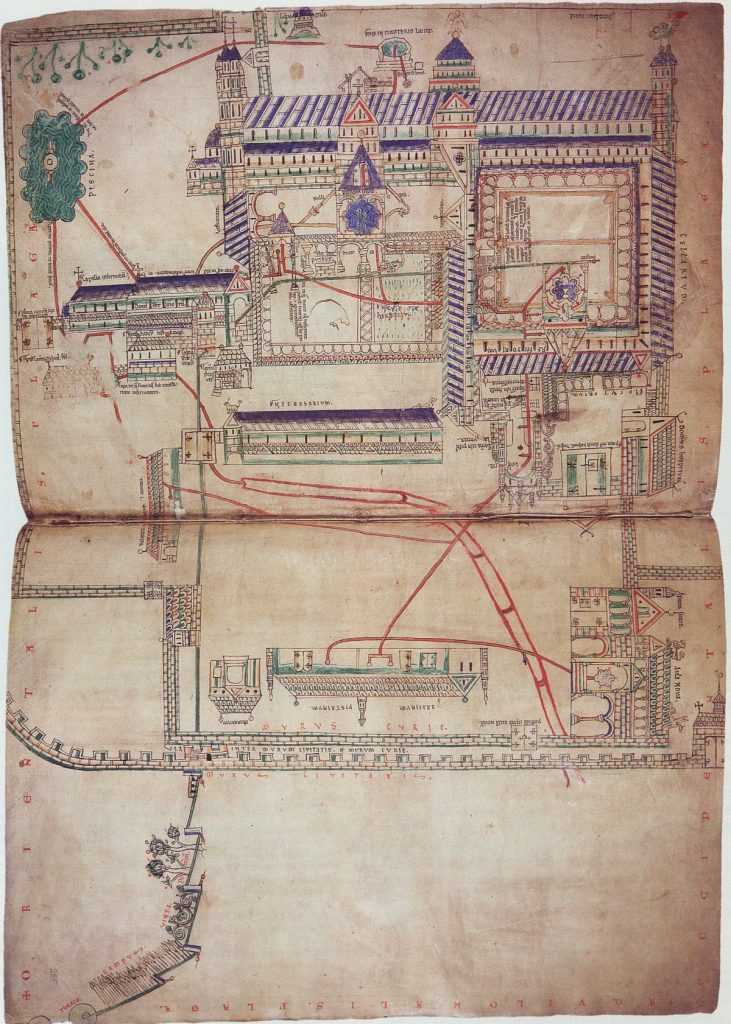

And if that wasn’t enough to make my head spin, today, professor Oosthuizen dug up and Tweeted this extraordinary c1160s map of Canterbury’s Christchurch Abbey in the Eadwine Psalter. As she explains, the drawing shows the complex managed passage of the monks’ water supplies into/across/out of the Abbey: from springs into holding tanks, then pumped into pipes passing through for example cloister fountains and basins, on their way to kitchens and latrines. The website Wyrtig provides a nice “reading assistance” for those not familiar with Medieval maps:

As in the kitchen courtyard, shown at left, buildings and other structures were portrayed as though you were standing in front of each facade. Pools and basins (lavers), in which the monks would wash their hands, were all drawn as if seen from above. The mapping of the water system was done with the heavy lines of inflow pipes and outflow drains dissecting the precinct and its structures.

Wyrtig

But most striking to me is how this remarkable document gives pictoral descriptions of the fields crossed by the conduit pipe between Military Road and the city walls: one could easily image him-/herself wondering this landscape, around the Abbey, past the wheat and vineyards, to pick up an apple from the orchard. I can almost hear the sound of my teeth taking a bite from it… and taste it, a little sour and bitter, but mostly sweet, and very very juicy… 😉

References

Adams, M. (2018). The Viking Wars: War and Peace in King Alfred’s Britain: 789? 955. Pegasus Books.

Birth, K. (2018). King Alfred’s Candles and Anglo-Saxon Time-reckoning. KronoScope, 18 (2).

Campbell, J. (2017). Placing King Alfred. In Alfred the Great. Routledge.

Maclear, G. F. (1888). S. Augustine’s, Canterbury: Its Rise, Ruin, and Restoration. Wells Gardner, Darton & Co.

Oosthuizen, Susan (2016). Culture and identity in the early medieval fenland

landscape, Landscape History, 37:1, 5-24, DOI: 10.1080/01433768.2016.1176433

Pratt, D. (2007). The political thought of King Alfred the Great (Vol. 67). Cambridge University Press.

Reuter, T. (Ed.). (2017). Alfred the Great: papers from the eleventh-centenary conferences. Routledge.

Richards, M. P. (2015). The laws of Alfred and Ine. In A Companion to Alfred the Great. Brill.

Roebuck, Judith (1997). St Augustine’s Abbey. English Heritage, 4-5.

0 Comments on “King Alfred & Canterbury”