We Vikings

Tomorrow, this “museum mouse” shall be in Leeuwarden, once again, to visit the Frisian Museum! Therefore, it seemed about time to publish an English translation of my review of their last exhibition, that was published in Kelten (*click*). Celtic/Viking art styles cheat sheet included! 😉

SUMMARY: The Frisian Museum (Leeuwarden) offered a notably nuanced view of the Vikings with its recent exhibition “We Vikings”. Aimed at a general audience, the exhibition stressed the many cross-cultural contacts and (trading) links between the Scandinavian and Carolingian world which came together in early medieval Frisia, as well as in the early medieval North Sea and Insular world at large. In her report on her visit to the exhibition, Martine Mussies stresses the further connections between the Scandinavian North and the Celtic West.

From 19 October 2019 to 15 March 2020, the Fries Museum (Leeuwarden) presented a ‘blockbuster’ exhibition: “We Vikings”. This exhibition sketched a nuanced picture of the presence of the looting Vikings in what was then Frisia – an area stretching from Belgium to Germany – from 810 A.D. After giving some background information about this exhibition and the purpose of the curators, I will tell you what made this exhibition extra fascinating for people interested in Celtic art and crafts.

The Vikings are hot. And no, I do not just mean the actors who play Ragnar, Rollo, Uhtred and consorts in the Netlix series. Viking Studies’ is also a flourishing field of research in the academic world. Medievalist Nelleke IJssennagger is one of the Dutch researchers who specialises in the Viking era. As curator of the Frisian Museum, she obtained her PhD at the University of Groningen in 2017 on the special position of Frisia in the Viking era. With her thesis “Central because liminal” she showed that in Frisia the world of the Vikings coincided with the world of the Franks. Her research was further developed and deepened by her successor (as curator) Diana Spiekhout. And that led to this exhibition: six rooms full of artefacts – many from the museum’s own collection, some borrowed – and a replica of the 15-metre-long warship Skuldelev V. This ship is impressively beautiful. Fast, light, manoeuvrable and flexible. Built by maritime engineering students of the ROC Friese Poort and decorated with shields made by Sebastiaan Pelsmaeker of RemainingHistory.com. The latter also provided various workshops at the exhibition, such as leather working and making a knife. On the wall behind the ship images were projected of the violence of nature, symbolising the stormy times. Children ran around the ship for the final assignments of their fun treasure hunt, on which they as young Vikings – with helmets and swords – went in search of their supposedly kidnapped Viking brother.

Just as Celtic language and culture students sometimes jokingly call themselves “Celts” in order to emphasize their solidarity, the Frisians of the museum wink at themselves as “We Vikings”. And with that emphasis on similarities instead of differences, the museum immediately dealt with a number of persistent prejudices. For instance, the Vikings are not a people. Of course Celtologists are also familiar with this discussion, but even if when you talk about “the Celts” you can still think of the collection of peoples and tribes who spoke a Celtic language (whether or not as their mother tongue), whereas the exhibition “the Vikings” presented the Vikings much more as separate people living in the same way of life, namely “on Viking” or on a raid. And both Scandinavians and Frisians took part in this. An interesting clue to this position can be found in one of the first pieces in the exhibition, a manuscript with the old Fivelguran and Oldambt land law about what has to be done “when the Vikings come and capture a man and bring him tied up to their ship, and then he sets houses on fire with them, in a village in his own country, and rapes women and kills men and does more harm…”. Spoiler, if he confesses and admits everything honestly, he will not be punished, because “as a servant he had to do what his lord commanded him to do”. The participation of the Frisians was also confirmed from the Scandinavian side, for example by the silver ornament with the inscription “We travelled to the brave people of Friesland and distributed the loot”.

Another prejudice is that the Vikings’ legacy would actually consist mainly of violence and destruction. This exhibition places these Scandinavians in a broader context of trade contacts between the various North Sea countries – a network that already existed before the Viking era, as evidenced by the many exotic stones and shells, the Rhineland ceramics and the Arab coins found in the Frisian mounds. Through a small loudspeaker, for example, visitors could listen to the story of the fibula of Wijnaldum, from around 625, which is decorated with pieces of red stone: almandine, from India. Conversely, the Frisians also exported raw materials and goods, such as the Frisian wool cloth. And in the Swedish trading town of Sigtuna, rune stones from the Viking era have been found as a memento of the Frisian guild members Albod and Torkel. One of the most curious pieces in the exhibition was the lost king, found in Leeuwarden. It is a somewhat smaller and coarser legged copy of one of the pieces by the Lewis Chessmen. Apparently, in the 12th century, the Vikings also played chess alongside hnefatafl (a board game related to the Celtic fidchell or gwyddbwyll). As far as decoration is concerned, the chess piece is less Viking than Romanesque and the rune-like marks on the side of the throne are probably a mark. Funny recognizable was the display case with Viking “toiletries” – combs, tweezers, small spoons and more. With this, the exhibition immediately disproved a third prejudice, which also appears in literature: the Vikings were not “barbarians” in the sense that they were unkempt. On the contrary: their fashion and hygiene inspired and influenced the Frisians.

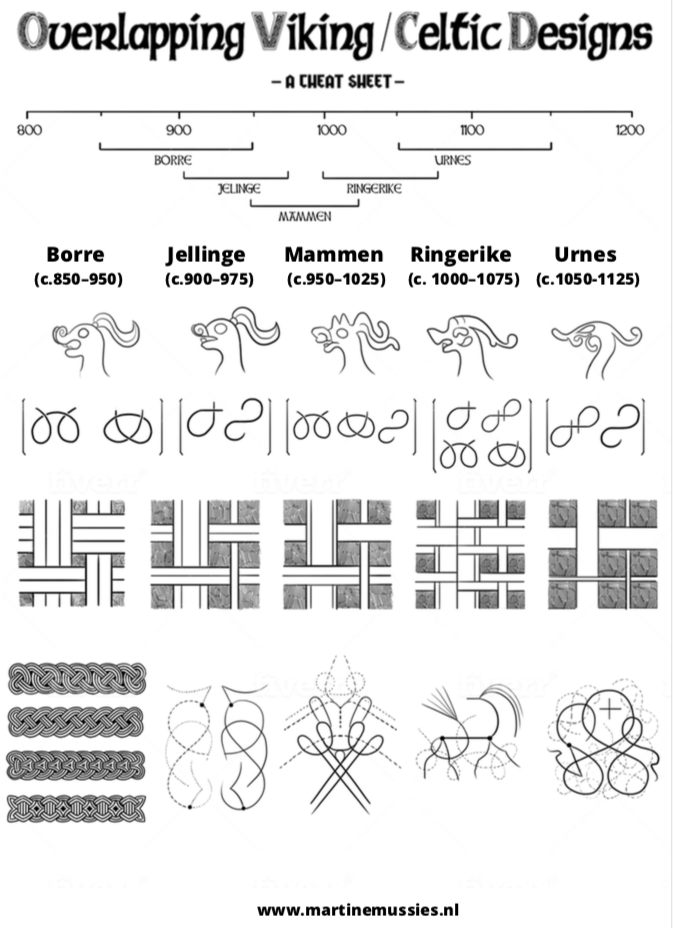

Anyone walking around the exhibition (in retro perspective) with a pair of Celtic glasses will recognise all kinds of decorations, for example from the insular manuscripts. The animal motif (a “grabbing animal” says the catalogue) on a coat pin, for example, which also comes back to the Scandinavian horn that was later used as a reliquary in the Basilica of Our Lady in Maastricht. It was made in the Jellinge style (popular between 900 and 975), which is characterised by this type of ribbon animal, usually with striped bodies, round or almond-shaped eyes, curled lips/ tongues and spiral/stalked necks. They are very similar to the various Celtic animals I encountered during my studies, for example in the Book of Kells. And the asymmetry of the long winding lines in the Scandinavian Urnes style (c.1050-1125) can be found for example in the Welsh Ricemarch psalter. Other styles of Viking decorations in which you can recognise Celtic influences are Borre, Mammen and Ringerike. Because these styles overlap in chronology, they cannot be used for accurate dating, but because of the design and recurring compositions and motifs you can quickly define and distinguish them. Borre is the earliest style (850-950) and these decorations can be recognised by the tight, knotty wickerwork, the symmetrical geometry (especially circles and squares), the triangular heads with the protruding flapping ears and the oval snout. You can also see this style on the crosses on the Isle of Man and on the fibula found in Swedish Birka. The Mammen style (popular between 950 and 1050) is named after the 10th century find in the Danish town of Mammen. The axe found there is decorated with a Celtic engraving inlaid with silver and the symbols can be explained in a Christian or pagan way. In this style you see many S- and pretzel forms, the “Great Beast” motif, masks and plants. The Ringerie style stands out because of the strange lobes and side lobes amidst the tight curves that only run in one direction, as on the famous abbot’s staff of Cúduilig (British Museum 1859.2-21.1). In addition, you see many pretzel nodes, rather coarsely drawn plant motifs and all heads and profiles. This style also had a great influence on the Winchester illuminations. In short: cross-pollination everywhere.

In addition to all these similarities, there are also clear differences. These can be seen, for example, in the diversity of knives from this period. During the workshop “Knife Making” by Sebastiaan Pelsmaeker we worked on a knife in Scandinavian style, based on the puukko from Lapland and Finland. “This knife is characterised by its straight back and flat, one-sided cut”, says Pelsmaeker. “In Ireland and Scotland, for example, you often see double-edged knives – actually daggers – or, as in the Saxon area, the Seax. That’s a knife with a single cut but a bent or kinked back”. Because the knives of this time vary so much in shape and size, it is sometimes difficult to bring them home. Then it helps to look at the material used for the grip. Pelsmaeker: “The workshop knife has a handle made of birch bark; this is typically Scandinavian because there, in the somewhat colder and woody climate, the birch develops a smooth and thick bark that is ideal for this type of handle. If no bark was used, the handle was often made of willow or (curly) birch. Often supplemented with pieces of moose or reindeer antlers. In the Celtic areas you find mainly knife grips of wood, especially yew and boxwood, often supplemented with horn and sometimes antlers. In the inland, the Carolingian area, you will also find wooden and horn handles, often complemented with metal decorations”.

My visit to the Frisian Museum was instructive and fun. Entering a replica of a Viking ship myself felt very different from reading descriptions, looking at pictures and empathizing with the Vikings on Netflix. By looking at the objects in “We Vikings” with “the Celts” in mind, I was able to place all kinds of elements in a broader context. Because fair is fair, upan hearing “Friesland”, I always thought mainly of mounds. And of the sixth-century king Hygelac from Beowulf. And thus to the complicated relationship between the Frisians and the Vikings. But with the North Sea as a high-speed line (certainly in comparison with transport over the swampy country), it’s hardly a surprise that Frisia was much more “multiculti” and there are also all kinds of Celtic elements and parallels.

Symke + I spent quite some time working on this birch bark knife handle, today, at a very interesting workshop by…

Geplaatst door Martine Mussies op Zaterdag 4 januari 2020

Wow. You sure know a lot about history! I just wish I can visit “We Vikings”. Do you think there would be a virtual tour?