Neo-medieval covers of game music

One of my favourite conferences is about the study of video game music aka ludomusicology. Last month, it was held again and to my great joy, I got to be the first speaker. Here’s a little blog made out of my notes from the presentation with YouTube videos of the music.

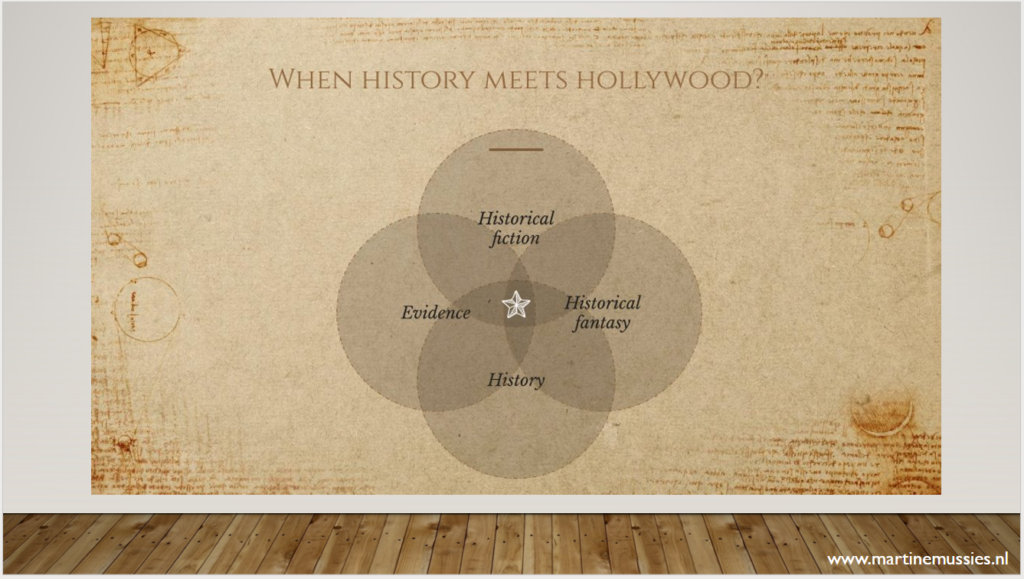

Today, I would like to talk with you about one of game sound newest Others: neo-medieval game music covers. With the popularity of neo-medieval music covering on YouTube – such as the bardcore genre – many game musics get a make-over in these styles, including game music. Often influenced by styles such as folk, rock, baroque, British folk rock and neofolk, many cover artists follow the popular strategy of combining medieval music with electronic music, influenced by bands such as Corvus Corax. Sonemic, Inc. (2021) notes that neo-medieval music originated in Germany from the neo-medieval movement. As Elmira Tanatarova (2020) explains by quoting musicologist Lisa Colton, the music represents nostalgia towards an older civilization. As such, she describes it as a mythology, reminding people of a more peaceful natural time.

In the forthcoming 20 minutes or so, I would like to share with you some of my explorations within this phenomena by combining musicological analyses with a fan studies approach, to conclude with two neo-medieval game music covers of my own – dedicated to King Alfred of Wessex. I would like to base these explorations of fannish musics on the framework I also use to analyze neo-Medieval fanfiction. My usage of the term “neo-medieval” will be similar to that in literary theory, as regarding the use and abuse of texts and tropes from the Middle Ages in postmodernity. The term neomedieval as a label to describe this phenomenon was popularized by the Italian medievalist Umberto Eco in his 1986 essay “Dreaming of the Middle Ages” and I think that this title says it all… 😉

Music for Alfred

People often ask me “why on earth are you playing songs for someone who has been dead for a thousand years!” . Hmm. First of all: it’s 1122 years, to be precise. And then to answer the question: because I think that by engaging in fannish behaviour from a neurodiverse perspective I can offer a meaningful contribution, thus opening up new possibilities within Anglo-Saxon (or Early English) studies. And on a more personal note, I could answer that it feels natural to me. One of the five love languages is “gift giving” and for me, that manifests itself in sharing my (modest) gifts, like making music. You could say that “music giving” is my love language. I make music for everything and everyone I love: for my family, for my friends, for my cat Boris and for the mermaids in my Phd thesis. As such, I also play music for King Alfred, a historical figure who fascinates me immensely, because of his combinations of thought and action, for example in his translation projects, political ideas and the stories around his harp playing.

Music from Alfred’s time

Initially, I wanted to play for Alfred the music that he could have known and might have recognized, if he were to hear me. But no musics that can be linked to him have survived. Of course, I know that he translated the first fifty psalms. Or at least he curated a translation of them, but as Thijs Porck already argued, the arguments for awarding it to Alfred are strong, as they concern both the language of the prose translations (a ninth-century West Saxon dialect) and a twelfth-century chronicler who notes that Alfred was working on a translation of the Book of Psalms, but had not been able to finish it before his death). So, these lyrics are there, but I have found nothing about possible chants for them – or any other texts from his period.

As for music from Alfred’s time and place… I did find some poetry that may also have been used as songtexts (writings of Bede and the fascinating Cædmon’s Hymn, for example), but no musical notation whatsoever. At the moment I am working on the Winchester Troper, but it seems that most of the pieces were newly composed / written by Wulfstan the Cantor, so that is too late. Of course, I also came across the beautiful antiphon dedicated to Boniface that Giovanni Varelli discovered and transcribed, but everything around it seems to resonate with traditions in Northwest Germany, and not with anything Insular.

Alas, I fear that I have to conclude that for the second half of the ninth century there is nothing musical surviving from Anglo Saxon England. It is very likely, though, that liturgical plainchant was the same as the one sung on the Continent. Moreover, one might get a bit closer to non-liturgical music with the reconstructions by Benjamin Bagby of the Beowulf as it may have been sung in the early Middle Ages. Sam Barrett at Cambridge has also worked on early medieval ’songs’ and there is some material online for that. But apart from these, however, there is very little surviving from that period.

Alfred’s musical afterlife

This is in stark contrast to the music linked to Alfred that was composed (well) after his death. Some of it is written by currently well-known composers such as Thomas Arne and Antonín Dvořák. The political implications of these opera’s were explained by graduate student Ryan Hall of the University of Toronto, in his fascinating talk entitled ‘Der Mann gehört uns an’ on King Alfred’s Operatic Afterlife and the Pan-Germanic Movement (online, August last year). But not much research has been conducted on the musical contents of these works. Thus, at the moment, I am digging up sheet music from these operas to play on the piano, so that we can hear how people have musically portrayed King Alfred over the years. And we can use these melodies to create new fannish interpretations of the music for King Alfred.

In the 20th and 21st centuries, a whole new genre emerged in Alfred’s music. Namely: the soundtracks of the movies, series, and computer games in which Alfred plays a role. Most melodies for 21st century Alfred are composed especially for the medium, like the beautiful music for the game Total War Saga: Thrones of Britannia, which includes taiko drums, ‘cellos, nychelharpas, a low whistle and a modern violin in scordatura. Its soundscapes are likely inspired by its precester, Total War’s other game about present-day United Kingdom through a medieval lens, which is Medieval II: Total War Kingdoms, from 10 years earlier. This was the expansion to the 2006 turn-based strategy PC game Medieval II: Total War and developed by Creative Assembly in 2007. I will play some snippets of both game musics to give you an idea about them.

Remixing

As you might have heard, these musics cleverly seem to blend the categories of our theoretic model and sometimes it seems as if this new music was based on an already older composition. This is often the case in the music connected to Alfred, for example in the well-known coronation scene in Netflix’ series Vikings, that was inspired by the sagas of Ragnar Lothbrok. In this scene, after a minute and a half, the “plain chant”-like vocals slowly drift to the background and a more tribal sound with percussion and later also vastly different vocals come in. Everything is connected in the neo-Romantic idiom of film music. Yet the beginning sounds like a piece of medieval music to our modern ears.

All that glitters is not gold and all that sounds medieval is not that old, but: this piece is! At first I thought it might be from the Winchester Troper (which would be a bit late historically, but stylistically appropriate), but I couldn’t find it in there. But then, the amazing Karen Cook told me she knew this piece, and that it is in fact an organum from the Musica enchiriadis – a 9th century anonymous musical treatise (once attributed to Hucbald), that is considered to be the first surviving attempt to set up a system of rules for polyphony in western art music.

The music for the Netflix series Vikings is thus a mix of original medieval material, performed in a historically informed way, mixed with film music (based on opera music) and intertwined with tribal elements. So it seems to be a new composition, loosely based on an older style. I really enjoyed this collage like method of composing, and that’s how I started playing, arranging and composing songs for Alfred myself. I think that this practice is important, for, also in music, storytellers fill the gaps, and Medievalism completes the stories that Medieval Studies write. Through our historical fantasies, we can help ‘Cherchez la femme’ as Barbara Olsen writes (2014). Her appeal to search out unknown women at the heart of a mystery, has as much relevance for the ongoing research of Early English history as it has for her own period of expertise, the Greek Antiquity, where, in her words, ‘so often women have been shrouded in myth, notoriety or obscurity.’

A folky version of CSM 10 with gymel

The tenth century leaves a lot of room for thought experiments in this realm, especially when imagining a Frankish princess visiting Anglia. If she were there on invitation, obviously, the receiving court would pull out all the stops to make her happy. Beautiful decoration of the hall, delicacies from far and wide, and: her favorite music. What could it be? A modest song, cheerfull melody, perhaps a well-known virelai or rondeau, maybe even one that would later be standardized in the Cantigas de Santa María? A “simple” (from a modern perspective) version of number 10, for example, the one with the beautiful melisms on the word “rose”. The Early English (“Anglo-Saxon”) musicians would play it their way, of course, following the traditions of the gymel technique to turn medieval monophony into polyphony. For example with a second voice in thirds above it, as explained by Early Music specialist Ian Pittaway. Played on harp-like instruments like the lyra and the cithara anglica and/or on fipple flutes made out of bone, wood or clay. But as we have little to no knowledge about the tuning system(s) of the Anglo Saxon music, we can never know how the gymel technique of polyphony actually sounded. To our “modern” ears, that are used to equally tempered instruments, it might sound out of tune, similar to instruments from folk traditions, such as the shvi I brought from Armenia. The result might well have sounded like this reconstruction:

Covering video game musics

You can, of course, do the same with the melodies from the 21st century representations of Alfred the Great: video games. And that brings us to today’s meat of the matter. Of course, just as playing older music on newer instruments, playing modern music on “old” instruments is nothing new. In the classical music world, compositions that are younger than the instruments they are played on are performed on a daily basis. This also goes for game musics on classical or baroque instruments. A quick search on YouTube brings up all kinds of funny videos, of people playing the Super Mario theme on harpsichord, such as the one from 2008, that we started off with, today. (Of course, this would have sounded very differently, had it been played in another authentic tuning of this historical instrument, such as Kirnberger III.) An extra layer is added to this, if the music that is played is in itself a reconstruction of an older music style, as for example in the soundtrack of neo-Medieval games like Mount & Blade and Crusader Kings.

This music I would categorise as historical fiction. Next to that, we have the musics for historical fantasy games like Baldur’s Gate. In this example, another layer in this “Spiegel im Spiegel” Droste effect is created when the neo-Medieval music is played on neo-Medieval instruments, such as through samples from a computer program. Then a completely new space is created in the so-called “Imaginary Medieval” – an imaginary-medieval music on an imaginary-medieval sounding instrument.

Through all kinds of musical markers, the 21st century audience might recognise the sounding result as a reference to the Medieval, but these musics would probably sound quite strange to a person living in the historical Middle Ages… 😉

In Music, Sound and the Multimedia, Jamie Sexton (2007) argues that all music for video is in essence a way to “represent environments in sound”. If that goes for all music in video games as well, I wonder whether there are audible differences between the sound tracks of games in the two modes of neo-Medieval representation as discussed: historical fiction and historical fantasy. Moreover, I would like to explore how these differences come into play through the fannish covers of these musics.

As many of the neo-Medieval games could be categorized as war games, their musics are often quite intense, and not like the Bardcore as described by Tanatarova, we started this exploration with. I do not hear nostalgia reminding people of happy times, I hear pumping, exciting and often epic soundscapes, in which the rhythm section is very present. This might have to do with the audience’s (conscious or unconscious) associations with tribalism, as seems to be the case for the music in Netflix’ series Vikings that I played earlier. But in video games, these drums might affect the player on a deeper level. Experimental studies in neuromusicology have already pointed out how rhythm relates to movement and emotion in the human brain. This provides some insight into the way game music might influence the player who will relate what they hear to what they see on screen, and by extension how these two stimuli relate to each other.

According to scholars like Kreutziger-Herr (1998), neo-medieval music reduces complex ideas about/from the Middle Ages into a decorative function that incorporates the period into contemporary vocabulary. But as I hope to have shown in this presentation, I think there is more to these neo-medieval game musics than meets the ear. Moreover, by creating their own versions of a piece of video game music, the musicians often also add a local flavor to the global musics, like the pentatonic accompaniments of Asian covers to the different tuning achieved by playing the games’ themes on the Indian bansuri. As these covers are often covered themselves, a whole new spectrum of “Droste”/”Spiegel im Spiegel” interactions across game-musical and cultural contexts thus arises.

Music for King Alfred

I would like to end this presentation by playing you some small fragments of two of the fannish neo-medieval covers of game music that I constructed myself, with many thanks to my producer WooTee who constructed the sound files from the instrumental samples. The first one of these covers would be more fitting in the historical fiction category, the other in the historical fantasy.

As a little disclaimer, I would like to add that this is by no means a critique towards the original game musics – as were they not historically accurate enough – but on the contrary, it is an adaptation as a step in the process of appreciation, with some added elements of what I think are the Bardcore / Tavernwave / neo-medieval audience’s assumptions of what constitutes the Imaginary Medieval.

The first one – composed for last year’s Interactive Pasts Conference – is based on the musics of two popular video games featuring King Alfred, but played only on the virtual versions of instruments that the Anglo-Saxon people knew. For example, the lyre that you hear only plays the notes that it was most likely tuned in. The harmonies are based on the Medieval gymel style (as discussed before), in which the voices move mainly in consecutive intervals of a third or a sixth, including the crossing of parts, that was so characteristic of the British Isles.

The second one – especially composed for this conference – was based on the intro music for Medieval 2 Total War Britannia, that I played for you earlier, with an added middle section. I have tried to make it epic in the way of a cinematic build up, by using some “tribal” percussion and adding chromatics in a more “Eastern” style.

Leave a Reply