An abridged version of this article was published in Hektoen International Journal of Medical Humanities.

Diagnosing Longing: A Medical and Cultural History of Nostalgia

“The past is not dead. It is not even past.”

— William Faulkner

Today, we often speak of nostalgia as a warm, bittersweet emotion—a longing for a bygone era, a childhood melody, or a photograph in sepia tones. Yet this modern sentiment belies a more severe origin: in the late seventeenth century, nostalgia was classified as a medical disease.

Coined by Swiss physician Johannes Hofer in 1688, nostalgia—from the Greek nostos (return home) and algos (pain)—referred not to poetic yearning, but to a diagnosable and potentially fatal condition of homesickness. It was observed in displaced soldiers who suffered from insomnia, lethargy, and cardiac irregularities, and was treated with bloodletting, purgatives, or ideally, a return home.¹ From this unusual beginning, nostalgia travelled far—through battlefield clinics, colonial outposts, Romantic salons, and psychological laboratories—until it emerged in the twentieth century as a complex psychological state with therapeutic potential.² This article traces that winding path.

Nostalgia as a Medical Disease

Hofer’s Dissertatio medica de nostalgia oder Heimwehe (1688) stands as the seminal text defining nostalgia as a diagnosable illness. He described soldiers who, after being sent far from their alpine homes, developed debilitating symptoms: loss of appetite, palpitations, fever, even risk of death.³ Hofer’s original case studies documented soldiers presenting with persistent weeping, anorexia, palpitations, and what he termed a “continuous vibration of animal spirits”. Physicians took detailed histories, noting whether patients fixated on specific landscapes, foods, or dialects from home. The diagnosis was often one of exclusion: when fever and wasting could not be attributed to typhus or consumption, and when the patient’s melancholy centred obsessively on return, nostalgia was recorded. Treatment protocols varied from the benign—music from the patient’s homeland, letters from family—to the severe: opium for agitation, purging for perceived toxic humours, and in extreme cases, threats of bleeding or burial far from home to “shock” the patient into acceptance. Yet the most consistently effective intervention remained repatriation, which physicians noted could produce near-miraculous recoveries within days of a soldier’s return. At a time when humoral theory still influenced medical thought, nostalgia was believed to disrupt the balance of body and mind. Treatments included leeches, opium, and dietary regimes; but the most effective cure was often repatriation.

This medicalisation of homesickness spread rapidly across Europe. During the eighteenth century, French and German physicians debated whether nostalgia was a form of melancholia or a distinct malady.⁴ By the Napoleonic Wars, military doctors were documenting thousands of cases, with nostalgia sometimes recorded as a cause of death. The severity of the diagnosis reminds us that what we call an emotion today was once framed as pathology, situated at the intersection of medicine, geography, and identity.

Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries

In the eighteenth century, nostalgia became a recognised condition among migrant populations and soldiers stationed abroad. Physicians noted its prevalence among Swiss mercenaries, German migrants in America, and soldiers in colonial campaigns.⁵ By the nineteenth century, advances in psychology shifted its framing from bodily disease to mental disturbance. Jean-Jacques Rousseau hinted at nostalgia as moral sentiment, while later physicians described it as akin to depression.

The industrial revolution and urban migration intensified experiences of dislocation, making nostalgia a common trope in literature and medical discourse.⁶ Yet it was also pathologised: excessive longing was considered unmanly or unpatriotic, particularly in militarised contexts. At the same time, emigrant communities often described nostalgia as a cultural bond, transforming it from an individual illness to a shared emotional condition.

Nostalgia and Colonialism

Nostalgia took on a different inflection in colonial settings. European physicians stationed in Asia and Africa considered it a climate-related illness, exacerbated by distance and environment.⁷ Colonial medicine thus absorbed nostalgia into its broader discourse on “tropical diseases.” Soldiers and administrators were thought to succumb to homesickness when deprived of their familiar landscapes and diets. Treatment, predictably, involved repatriation or the temporary “import” of European comforts.

At the same time, nostalgia was framed in racialised terms: non-European peoples were considered either immune or susceptible in different ways, depending on the prejudices of the time.⁸ This not only medicalised homesickness but also embedded it in the power dynamics of empire. Nostalgia thus reveals how emotions were mobilised to sustain colonial hierarchies, justifying European fragility while questioning the resilience of colonised populations.

The Romantics and the Arts

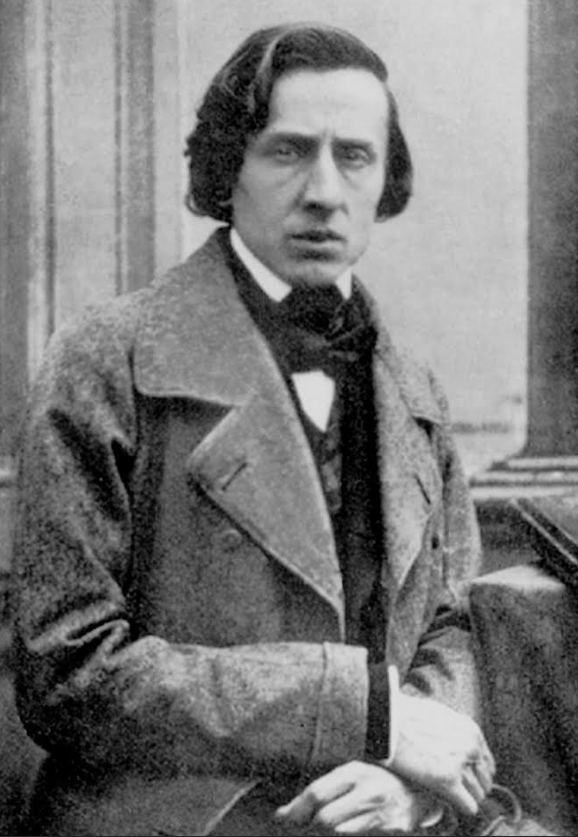

The nineteenth century also witnessed nostalgia’s transformation from malady to aesthetic category. The Romantics embraced longing as a source of creativity. Goethe’s Die Leiden des jungen Werthers epitomised a new cultural sensibility where yearning for the unattainable became noble rather than pathological.⁹ In music, composers such as Frédéric Chopin crafted works infused with melancholy, their harmonic choices evoking loss and longing. Chopin’s mazurkas, written in exile, exemplify how nostalgia for homeland could be transmuted into art, as commentators note that the rhythmic patterns and modal inflections evoke the spirit of a Poland lost to partition and memory.¹⁰

Gothic nostalgia continues the Romantic tradition of melancholic longing, yet reframes it through a feminist and disability-aware lens. Fanfictional reworkings of mermaids, for instance, reimagine longing and loss in embodied, intersectional ways—where nostalgia becomes not a sickness, but a reclamation of agency by the misfit, the hybrid, and the disabled heroine.²⁰

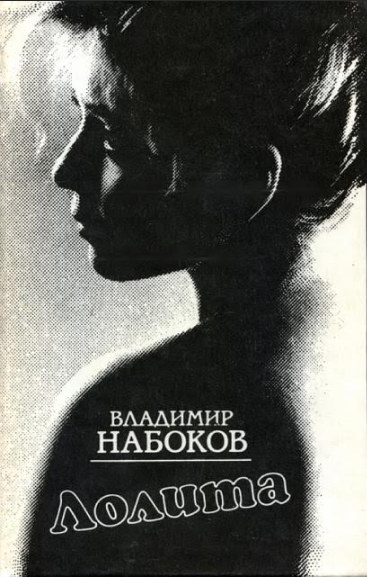

Similarly, literary modernism inverted nostalgia’s moral valence. Nabokov’s Lolita offers a disturbing parody of the nostalgic impulse: Humbert’s longing for an idealised childhood corrupts the very language of innocence. Nabokov’s synaesthetic prose entwines sensory pleasure with moral decay, transforming nostalgia for youth into an act of possession—a perversion of memory itself.¹¹

Painters and poets alike reframed nostalgia as a form of sensibility, linked to memory, imagination, and identity.¹² Whereas physicians sought cures, artists cultivated the very symptoms medicine condemned. Nostalgia thus entered salons, concert halls, and literary circles as a refined sentiment, aligning with the Romantic valorisation of subjectivity. Its journey from battlefield to art gallery reveals the porous boundaries between medicine and culture, showing how one era’s disease can become another’s muse.

Twentieth and Twenty-First Centuries

Nostalgia’s disappearance from medical textbooks was gradual rather than sudden. By the late nineteenth century, advances in bacteriology and the rise of psychiatric classification began to dismantle humoral frameworks. Nostalgia became increasingly difficult to locate within new taxonomies: it was not infectious, not hereditary, and its symptoms overlapped uncomfortably with neurasthenia, melancholia, and what would later be termed depression. The term persisted in military medical records through the First World War, but by the 1920s it had been effectively reclassified as a psychological phenomenon rather than a distinct disease entity. Medicine had not disproved nostalgia; it had simply outgrown the conceptual architecture that made homesickness legible as pathology.

By the twentieth century, nostalgia was no longer recognised as a medical diagnosis but persisted as a psychological phenomenon. Migrants, exiles, and veterans continued to experience its pangs, yet psychologists began to study it as a cognitive-emotional state. Early research pathologised nostalgia as a regressive longing.¹³ However, later studies reframed it as adaptive. Work by Constantine Sedikides and Tim Wildschut demonstrated that nostalgic reflection fosters self-continuity, increases social connectedness, and even buffers existential anxiety.¹⁴

In recent decades, neuroscientific research has confirmed that nostalgic memories activate reward pathways in the brain, particularly the prefrontal cortex and hippocampus.¹⁵ Rather than being purely painful, nostalgia can combine sadness with comfort, producing a bittersweet affective state.¹⁶ Its therapeutic potential has been recognised in clinical settings, where guided nostalgic reflection can alleviate loneliness among the elderly or support identity work among migrants.

Nostalgia, however, often engages with borrowed pasts. In popular culture, many forms of retro-aesthetic evoke eras the audience never personally lived through. The depiction of mid-century American cars and domestic interiors in Belgian comics such as Suske en Wiske reveals a mediated nostalgia—one rooted not in memory, but in aspiration and cultural imagination.¹⁷ Such nostalgia for someone else’s past reflects the way global media recycles the aesthetics of previous decades to evoke belonging and continuity.

Reflection and the Digital Age

In the twenty-first century, nostalgia extends beyond psychology into technology and art. Digital tools now enable the simulation of past aesthetics, producing what might be termed synthetic nostalgia. Artificial intelligence, for instance, can re-render contemporary photographs into the colour palettes of the 1970s, complete with grain and fading. Such images appeal not only to those who lived through the decade, but also to younger generations who never experienced it directly. Why? Because nostalgia is as much about imagination as about memory.¹⁸

Just as Welsh hiraeth describes a longing not only for a lost home but for one that may never have existed, our modern digital nostalgia often seeks imagined pasts rather than lived ones.¹⁹ Hiraeth captures “a deep yearning, tinged with grief and hope, for a home that exists as much in the imagination as in memory.”²¹ This sense of Fernweh and Hinausweh—longing for something beyond reach—resonates profoundly with the way artificial intelligence now reconstructs the past. When I transform a Slovenian landscape into a 1970s postcard, it is not merely nostalgia, but hiraeth: a creative ache for a world that feels familiar yet was never truly mine.

The inversion is complete: nostalgia, once treated as a disease to be expelled, is now prescribed as medicine for the dislocated self. Far from a disease, nostalgia has become an aesthetic, psychological, and technological resource—an enduring testimony to the ways humans navigate time, place, and belonging.

References

- Johannes Hofer, Dissertatio medica de nostalgia oder Heimwehe (Basel, 1688).

- Thomas Dodman, What Nostalgia Was: War, Empire, and the Time of a Deadly Emotion (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2018).

- Dodman, What Nostalgia Was, 22–45.

- Krystine I. Batcho, “Nostalgia: The Bittersweet History of a Psychological Concept,” History of Psychology 16, no. 3 (2013): 165–176.

- Dodman, What Nostalgia Was, 90–112.

- Svetlana Boym, The Future of Nostalgia (New York: Basic Books, 2001).

- Mark Harrison, Medicine in an Age of Commerce and Empire: Britain and Its Tropical Colonies, 1660–1830 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010).

- Harrison, Medicine in an Age of Commerce and Empire, 134–150.

- Goethe, Die Leiden des jungen Werthers (1774).

- “Mazurkas – Fryderyk Chopin,” Culture.pl, last modified 2016, https://culture.pl/en/work/mazurkas-fryderyk-chopin.

- Martine Mussies, “Лолита и синестезия: Сравнительный анализ английского и русского переводов [Lolita and Synesthesia: A Comparative Analysis of the English and Russian Translations]” (Master’s thesis, Saint Petersburg State University, 2009).

- Boym, The Future of Nostalgia, xv–xxiv.

- Batcho, “Nostalgia,” 168.

- Tim Wildschut, Constantine Sedikides, et al., “Nostalgia: Content, Triggers, Functions,” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 91, no. 5 (2006): 975–993.

- Clay Routledge et al., “The Past Makes the Present Meaningful: Nostalgia as an Existential Resource,” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 101, no. 3 (2011): 638–652.

- Routledge et al., “The Past Makes the Present Meaningful,” 641.

- Martine Mussies and Wouter Steenbeek, “Humane but Not Human: Robots in Suske en Wiske.” Foundation 54, no. 150 (2025): 98–111.

- Batcho, “Nostalgia,” 172.

- Pamela Petro, “Dreaming in Welsh,” The Paris Review (2012).

- Martine Mussies, “Toxic ableism and gothic nostalgia in fanfiction about mermaids,” in Gothic Nostalgia: The Uses of Toxic Memory in 21st Century Popular Culture, 225–243 (Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2024).

- Martine Mussies, “Welshe weemoed,” in Kelten: Jaarboek van de Stichting A. G. van Hamel voor Keltische Studies 1 (2017): 17.